Abstract

Multimodal generative Artificial Intelligence is an omnipresent technology in our post-industrial societies, as it has penetrated all areas of daily life, from social and commercial relations to the various fields of science and industry, communication, leisure and culture in general. This is to discuss whether AI is applicable to the field of artistic creation in general and to bodily arts such as dance in particular, taking into account emotional sensitivity and creativity, factors that are difficult to generate by a machine. In this article we will discuss examples of corporal artistic manifestations, in the domain of dance, in which corporality itself is called into question in the face of these interactions with humanized bodies conceived, created and “brought to life” by the magic of generative AI. The learning models developed by different Artificial Intelligence software allow these bodies to dance, model or evolve in scenographic spaces created ad hoc and shared to the point of replacing real dancers.

-

Keywords: Semiotics, Artificial Inteligence, Dance, AI-Dance, IArt

1. Introduction

Multimodal generative Artificial Intelligence is an omnipresent technology in our post-industrial societies, as it has penetrated all areas of daily life, from social and commercial relations to the various fields of science and industry, communication, leisure and culture in general. The generative models that surprised us at the beginning of this decade are giving way to much more sophisticated intelligent hyperautomation systems, the so-called Operator Agent from OpenAI.

The applications of AI algorithms and big data engineering are very useful for the advancement and progress of humanity in sectors such as healthcare (genomic mapping, clinical diagnosis, personalized treatments in oncology), advertising and consumption (targeted prescriptions, audience measurement), office automation, robotics and home automation (voice assistants, robots for different tasks), security and cybersecurity (geolocation, facial recognition, image and data analysis)... but they also intervene today, to an increasing extent, in the field of the arts, a field apparently exclusive to creative human capacities.

Artistic creation, in fact, seems to be exclusive to natural human intelligence, insofar as it is produced from emotionality, a non-rational component that could hardly be generated by a machine. Art represents one of the insurmountable frontiers for generative artificial intelligence models due to these two closely linked conditions: emotional sensitivity and creativity.

2. IArt and creativity

What until a little over a decade ago was evident, the impossibility of AI tools to break through the barrier of creative capacity by working with pre-existing databases (

Jennings 2010), seems to have been overcome in recent years with the dizzying evolution of these tools and cognitive models that show an extraordinary capacity for learning, combination, relationship and cloning.

Natale and Henrickson (2022) believe that a different concept of creativity should be applied to refer to

computational creativity, described in terms of what they call the

Lovelace Effect, that is, creativity would not be an inherent quality of software but a subjective effect felt by human receptor-users who interact with machines, regardless of the intentions of their enunciator-designers, according to their horizon of expectations and based on their technical, social and cultural contexts (2022, 16-17). In this specific sense, we can say that AI is creative:

The Lovelace effect represents a reevaluation of Lovelace’s contribution that responds to more recent efforts in areas like computational creativity that emphasize the role of human users in attributing qualities such as intelligence, agency, and originality to machines. The Lovelace effect, in this regard, puts forth a concrete analytical tool for mobilizing these efforts by describing situations in which the behavior of computing systems is perceived by users as original and creative (

Natale and Henrickson 2022, 9).

We must distinguish between a) conventional arts that use Artificial Intelligence tools and b) what is called

Artificial Intelligence Art, AI Art, which I have called

IArt (

Paz Gago 2024). This second type refers fundamentally to audiovisual art created exclusively with AI, when

AI is used for creative purposes and generating novel artworks (

Cetinic and She 2022), different from the applications of Artificial Intelligence implemented in conventional arts in which the human artist makes use of his own tools (cameras, brushes, pencils, musical instruments...).

If in the first type (a), of a hybrid nature, the original creativity is ensured by the action of the human being, who controls the entire process, Cheng strongly reaffirms the creative nature of the second type (b):

AI art is artistically creative (2022). In fact, some specialists predict that cognitive generative technology will have achieved full scientific and artistic creativity, similar to that of humans, by 2030 (

cfr.

Cabanelas 2019).

This is the most controversial aspect of the discussion, since creativity in its literal sense is difficult to apply to IArt today, as defended by

Kirkpatrick (2023) for whom AI uses pre-existing data and works, combining them in an innovative way, perhaps, but on already existing elements, the so-called

Lovelace Objection evoked by

Natale & Henrickson (2022). We could not call this process creative, an inherent and exclusive capacity of the human being, subject to emotions and feelings that machines cannot experience (

Kirkpatrick 2023, 23). To achieve full and literal creativity, further evolution of AI technology is necessary, as Cheng argues, in line with Cetinic and She:

Although AI art is often critiqued on the basis of creativity, this study established that AI art is artistically creative. This paper suggests that people who are committed to AI art are in the right place because by doing so, they have the opportunity to explore new AI technologies, discover the potential of a human’s psychological process of creating art as re-embodied via computational abstraction processes, and actually make new forms of art (

Cheng 2022, 5).

In any case, the truth is that, beyond its practical applications in facilitating the daily lives of human beings, it is precisely in the field of artistic experience where AI is achieving the most surprising, hitherto unsuspected results. With the debate evoked here on the limits of these background applications, particularly on the so-called AI creativity – an indisputable reality for Cheng (2021), an impossibility for

Jennings (2010) or

Kirkpatrick (2023), a possibility with certain nuances for

Natale & Henrickson (2022) – artistic expressions that work with the human body (Body Arts) interact today with non-human virtual bodies in an increasingly precise and perfected way, causing hitherto unknown phenomena of interaction/confusion/hybridization.

3. Dance and AI

In the audiovisual arts, there are already countless creative tools that generate entirely or collaborate with artists in music, film, video, design, architecture or painting, such as AdCreative.ai, AI Art Generator, NVIDIA Canvas, DALL-E 3, Midjourney, StarryAI or Flux, both to transform text into images and to create, format, sketch or color them, combining them in a truly innovative way.

Our interest focuses on arts that involve the bodily participation of the human being, increasingly disembodied, in interaction with non-human beings generated by AI: actors, dancers, mannequins, real and virtual, that coexist on the stage or on the fashion catwalk or are even replaced by these.

In recent decades we have witnessed a process of transformation of the spectacle due to the invasion of audiovisual technologies, first analog and then digital, that have reconfigured the very nature of live performances. Actors, performers, dancers are replaced or coexist in the same stage space with their avatars, these new entities that I have called

avactors (

Paz Gago 2018), which occupy the post-contemporary scene of the new millennium. In the case of dance, Élodie Verlinden firmly states that the human element is crucial, pertinent and even indispensable (2016, 65), so dancers could not be replaced by artificial beings, which is why the belgian researcher expressly rejects, in the dance scene, non-living bodies such as automatons, projections, holograms or robots.

But whether we like it or not, the very nature of live performing arts, which feature the human body and its corporeal presence, has radically changed. After the crisis of representation that the 20th century already saw, the boundaries between the physical body and the media image, between corporeal reality and virtual reality, have now become blurred. Today, there has been a crisis of physical representation, as the threshold between the real and the virtual has become imprecise, producing a dissociation of the corporeal and material co-presence of the actor and the spectator (

Helbo 2022, 18). AI would be nothing more than a new step, even more radical if possible, in this critical process.

In this article we will discuss examples of corporal artistic manifestations, in the domain of dance, in which corporality itself is called into question in the face of these interactions with humanized bodies conceived, created and “brought to life” by the magic of generative AI. The learning models developed by different Artificial Intelligence software allow these bodies to dance, model or evolve in scenographic spaces created ad hoc and shared to the point of replacing real dancers.

3.1 Human-Ai Co-creation of Dance (England 2022)

Human-Ai Co-creation of Dance is a interesant project developed in 2022 by the Center for The Future of Intelligence at Cambridge University, in which the mexican choreographer Diego Marín execute a live dance performance sharing space with an artificial intelligence dancer, an hybrid experiment precisely around Creativity in Human/AI interaction.

It was a co-creative performance that combines the live regime with a digital, artificial-virtual regime, through images created with AI software, that dancer developed by Benedikte Wallace of Oslo University, which raises questions that are both semiotic and artistic as well as philosophical and anthropological, in the line of posthuman ethnography and anthropology.

The peculiarity of this initiative compared to other AI Dance experiences (

Paz Gago 2024b) is precisely the research on creativity since it is based on collaboration with AI as a creative agent and not as a simple tool. The great challenge here is to go beyond generative AI to reach Creative-Interactive AI. With this project, the LCFI at Cambridge University, founded by physicist Stephen Hawking, sought to explore the interaction between human and non-human beings (is this even a "being"?), between art and technology, art created by humans and art generated by machines.

The Human-Ai Co-creation of Dance Project attempted to deepen the knowledge of human intelligence linked to the corporal and carnal component in its creative interaction with virtual bodies, with a material component different from the human one. But the results so far are very poor, not going beyond a pure digital schematic representation of the movements performed by the human dancer

1.

Perhaps due to the underdeveloped state of AI applications and tools three years ago, in 2022, in a technology that advances spectacularly from month to month, Human-Ai Co-creation of Dance has not yielded the expected results and has failed to demonstrate the creativity of IArt in artistic expressions that work with the body, both on their own and in interaction with human agents.

In my opinion, in the case of dance, body art par excellence, what should be considered is the possibility of the participation of artificial dancers in the creation of artistic movements following a certain choreographic notation and a certain musical score, and from there introduce creative variations.

3.2 Nondance Dance and Nondance Dance 2 (South Korea 2022, 2024)

Particularly interesting is the Nondance Dance experiment by Korean choreographers and dancers Chung Ji Hye, Kang Seong Ryong, Shin Seung Back and Kim Yong Hun, produced by the Korea National Contemporary Dance Company also in 2022. This scenic proposal was presented as part of the Dance X Technology Project at the Sejong Center for the Performing Arts S Teaheater on September 25, 2022.

This curious pioneering performance is based on Google Video AI technology and recognition systems through which dancers search for a dance form that an AI observer-camera tries to recognize as non-dance or as dance, such as one of the basic recognizable dance categories (classical ballet, flamenco, country, folk, hip hop, salsa, tango...).

Through a series of parameters both scenic – set design, costumes, lighting – and kinesthetic – shape, speed, position – the AI can recognize each category of dance and those performances that Nondance considers, giving its response through the use of voice and light or darkness. According to the creators of this performance, their goal was to rethink the relationships between dance and humanity, seeking dance exclusively for humans.

This project will be continued in Nondance Dance 2, presented as an installation at the Daejeon Museum of Art, during the Daejeon Art and Science Biennale, in 2024. An indeterminate series of videos are projected on large screens in which the dancers perform movements and postures that do not conform to the conventional codes of dance – stuck to the floor or the wall, without rhythm, closer to sport than to dance, convulsions, etc. – so that the AI observer, equipped with a 4-channel video installation system for detecting and recognising actions, can give his verdict through smaller screens placed in front of the main screens. This response shows how the AI interprets the movement as dance or not dance, both in the form of low percentages of similarity with dance or directly in total darkness, which means that it identifies these movements with human dance.

3.3 Human-AI Co-Dancing (Thailand ant Taiwan 2024)

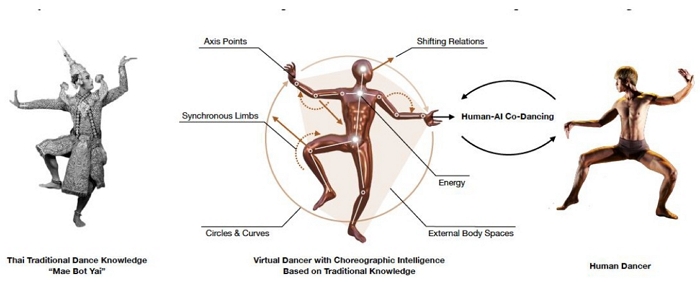

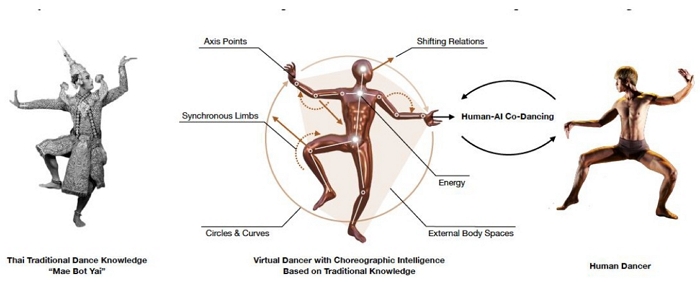

Much more technologically advanced is the project of traditional Thai folk choreographies in which generative virtual characters are integrated. Led from the MIT Media Lab by researchers Pat Pataranutaporn and Pattie Maes, in collaboration with creators and dancers from the Pichet Klunchun Dance Company, Human-AI Co-Dancing seeks to synthesize Thai choreographic heritage into interactive computer models.

In recent years, there have been countless proposals for interaction between human and non-human actors and dancers generated by artificial intelligence, which have been presented in different countries: Deep.Dance by Jascha Viehstädt in Germany, Coreograf-IA by Victoria Riva in Spain, Human in the Loop by Nicole Seiler in Switzerland, Body Fail by Jean Marc Matos in France, Nondance Dance and Nondance Dance 2 by Chung Ji Hye, Kang Seong Ryong, Shin Seung Back and Kim Yong Hun in South Korea.

Human-AI Co-Dancing describes a series of choreographic principles on which traditional Thai dance is based, in a very prototypical way, and systematizes them in computational procedures to transfer them to the joint movements of a digital actor. Beyond the classic video recordings of dance performances, this resulting model

as a form of "artificial intelligence" system because it aims to encode the "choreographic intelligence" of traditional dances into a computational model capable of responding and choreographing with human dancers in real-time (

Pataranutaporn et al. 2024, 2).

From the six choreographic principles of Mae Bot Yai – Energy, Circles & Curves, Axis Points, Synchronous Limbs, External Body Spaces, and Shifting Relations – that define the fundamental poses traditional Thai dances for Pichet Klunchun, a methodology is developed in 4 phases: 1) Capturing Movement Data, 2) Encoding Choreographic Intelligence, 3) Interface Development & System Integration and 4) Rehearsing Human-AI Co-dancing.

It is this last phase that interests us most because of its semiotic and artistic relevance, as well as its consequences for possible creativity:

Collaborative performances and exercises utilizing this technology explore new choreography through human-AI interaction. These endeavors act as an experimental research platform for the future of dance (

Pataranutaporn et al. 2024, 4). In the experimental performance presented at the National Theatre of Taiwan in March 2024, the creative potential of Human-AI Co-dancing was explored in depth. The interaction of human and artificial dancers during improvisation demonstrated that they reacted to each other's movements and, most importantly for the creative dimension, it was shown that

the virtual character exhibited new responses generated algorithmically from traditional choreographic knowledge (

Pataranutaporn et al. 2024, 6).

Once the goal of generating an interactive system (Human Computer Interaction, HCI) to allow real dancers to improvise in interaction with virtual dancers has been achieved, it is truly fascinating to see how new and unprecedented possibilities arise from this true syntax of movements and poses created by the choreographers and artists of Pichet Klunchun Dance Company. In what they call intriguing frictions, produced in this interaction, lies the key to the creative potential of artificial intelligence:

As the human dancer physically challenges, resists, follows, and improvises with the virtual dance partner’s computational interpretations of traditional dance vocabularies, intriguing frictions arise that highlight each intelligence’s distinct perspectives and capabilities. This dynamism suggests rich questions around autonomy, influence, control, and co-dependence as humans and virtual agents entangle through points of resonance and dissonance. Such interplay prompts vital discourses on the essence of the human spirit and freedom when choreographically coupled with non-human outputs operating in the same social and cultural space (

Pataranutaporn et al. 2024, 7).

There could be a dance show, virtual dancers could coexist, created and trained by multimodal generative AI tools, their performance could allow for a margin of improvisation that we could even consider creative... but human choreographers and dancers will always have to take the initiative, on whom the intellectual and artistic capacity of innovative creativity depends so far.

4. Semiotic Mode od IArt: Machination

Our research will focus on defining the semiotic modality of this radically disruptive techno-communicational phenomenon which, in contrast to the Representation characteristic of analog media and the Simulation characteristic of digital media, will be defined based on the concept of Machination. We propose this term for its double semantic value of machine and deception, both meanings that agree well with the models replicated by multimodal generative AI. In English, as in other languages, the lexeme Machination implies both the semes intrigue, plot, trick, device (Collins English Dictionary) and the semes derived from its etymological root, Machine, defined as any mechanical or electrical device that automatically performs or assists in performing tasks, a meaning that agrees perfectly with AI.

Still relatively undeveloped in a technological framework that is just emerging but is advancing at a dizzying speed, the AI Dance experiences analysed here, featuring virtual dancers interacting with real dancers, are not very convincing either aesthetically or creatively. The cases we have considered in this article are mere experimental proposals that demonstrate neither intellectual, artistic nor creative capacity on the part of the artificial agents and the machine that generates them, whose intelligence and imagination are for the moment determined by human intelligence and imagination. The impression of a certain creative potential in these dances is a mere mirage, the fruit of what I have called a Semiotic Machination.

Notes

REFERENCES

- Ali Elfa, M. A., and M. E. T. Dawood. 2023. “Using artificial intelligence for enhancing human creativity”. Journal of Art, Design and Music 2 (2): 3.

- Bryndin, E.. 2019. “Practical development of creative life-saving artificial intelligence”. Communications 7 (2): 31-39.

- Cabanelas, José. 2019. “Inteligencia artificial ¿Dr. Jekyll o Mr. Hyde?”. Mercados y Negocios 1 (40): 5-22.

- Cetinic, E., and J. She. 2022. “Understanding and Creating Art with AI: Review and Outlook." ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing”. Communications and Applications 18 (2): 1-22.

- Cheng, M.. 2022. “The creativity of artificial intelligence in art”. In Proceedings of The 2021 Summit of the International Society for the Study of Information 81 (1): 110. https://www.mdpi.com/2504-3900/81/1/110

- Helbo, André. 2022. Lire le spectacle vivant. Bruxelles: Académie Royale de Belgique.

- Jennings, K. E.. 2010. “Developing creativity: Artificial barriers in artificial intelligence”. Minds and Machines 20 489-501.

- Kirkpatrick, K.. 2023. “Can AI demonstrate creativity?”. Communications of the ACM 66 (2): 21-23.

- Natale, S., and L. Henrickson. 2022. “The Lovelace Effect: Perceptions of Creativity in Machines”. New Media and Society 1-27. //efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/182906/6/NMS-20-1531.R2_Proof_hi%20%282%29.pdf

- Pataranutaporn, P., P. Maes, P. Mano, T. Chongchadklang, and et al. 2024. “Human-AI Co-Dancing: Evolving Cultural Heritage through Collaborative Choreography with Generative Virtual Characters”. MOCO '24: Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Movement and Computing 14 1-10.

- Paz Gago, José María. 2018. “Acteurs, Avatars, Avacteurs. La théâtralité à l’ère du posthumain.". Degrés 175-176: d1-d13.

- Paz Gago, José María. 2020. “De la représentation à la simulation. Modes de représentation du spectacle post-contemporain.". Degrés, 180-181: e1-e14.

- Paz Gago, José María. 2024a. "IArt-à-porter: la moda en la era de la Inteligencia Artificial.". MATRIZes 18/3: 85-96.

- Paz Gago, José María. 2024b. "La danse à l'ère de l'IA. Coppel-I.A. au Ballet de Montecarlo." (Nouvelles) Épidemies dansantes. Danse par/pour toutes?. Charleroi: Université Libre de Bruxelles (sous presse).

- Verlinden, Élodie. 2016. Danse et spectacle vivant. Réflexion sur la construction des savoirs, Bruxelles: Peter Lang.

Figure & Data

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by