Abstract

Our study proposes a socio-relational approach intended to inform the training of an artificial intelligence system for botnet detection. First, a corpus of accounts likely to be automated was assembled using individual criteria defined by the Beelzebot team (Brachotte et al.). These accounts were then analysed through their interaction dynamics in order to identify relational configurations that could serve as relevant signals for automated detection. The article presents a socio-relational analysis based on a three-step protocol: (1) identifying forms of self-interaction; (2) examining internal interactions among suspected accounts; and (3) analysing their external interactions with third-party actors. Conducted within the framework of the ANR Beelzebot project, which aims to develop the first French-language solution capable of detecting information manipulation strategies deployed by automated networks in the French-speaking X-sphere, this research constitutes an exploratory phase designed to calibrate the data-preparation methodologies required for training an AI model that integrates socio-relational indicators. In addition to producing a quantitative score, our model aims to provide a complementary qualitative output that offers insight into the characteristics of the botnet and the functional roles occupied by different bot profiles within the network. From an ethical standpoint, this approach contributes to the development of a more explainable AI model.

-

Keywords: botnet detection, socio-relational analysis, explainable AI, interaction dynamics, ethical issues in AI.

1. Introduction and research questions

Contemporary socio-technical devices - such as X, Facebook and Instagram - now occupy a central place in the information ecosystem. Their massive use, exceeding five billion users in 2025, attests to their structuring role in the dynamics of information, socialisation and mobilisation (

We Are Social & Meltwater, 2025). Far from being mere dissemination tools, they shape social practices by producing socio-technical environments where forms of visibility, interaction and attention are redefined (

Boyd & Ellison, 2007;

Ellison & Vitak, 2015). They thus contribute to the reconfiguration of digital public spaces and contemporary modes of expression of controversy. In this environment, social networks are no longer solely the theatre of human interactions: they also host forms of social automation that alter the conditions under which information circulates. Bots-software agents that mimic human behaviour-are now a structural component of these platforms. In 2022, Twitter acknowledged that approximately 5% of its active accounts could be automated, while Elon Musk publicly mentioned up to 20–25% when he acquired the platform. Estimates produced by independent research have since converged on a proportion of 10–20% of automated accounts: approximately 9–15% according to Indiana University and Ferrara's team, 13% according to Cyabra (2023–2024), and nearly 20% according to CHEQ (2023). But even more than their digital presence, it is their disproportionate activity that characterises these agents: several recent analyses show that a minority of bots can produce 30–40% of the visible flow in certain debates, and up to 45% in high-profile controversies (Cyabra 2024; CHEQ 2023; Stanford Internet Observatory 2024). Their increasing sophistication, reinforced by the rise of generative AI (

Najari et al., 2024), enables them to produce credible content, adopt human temporalities, and intervene in dynamics of amplification, polarisation, or informational manipulation (

Ferrara et al., 2016;

Grinberg et al., 2019;

Ferrara, 2020). In the French-speaking context,

Brachotte (2025) shows that they exploit the affordances of X to generate misleading relational signals, alter perceptions of engagement, and fragment public space. The effectiveness of these agents is partly due to their socio-technical agency: bots do not have their own intentions, but they nevertheless produce social effects because they update, in a given context, technical scripts embedded in the platform's architecture. Their action is distributed: it results from an interplay between their programming, the affordances of X, the algorithmic logic of recommendations, and user practices. Thus, their intervention is not limited to the autonomous transmission of content, but is part of a broader interactional dynamic, where they contribute to reconfiguring relationships, circulations, and visible signals.

This dynamic is particularly pronounced on X, a platform structured around real-time visibility. The work of

Himelboim et al. (2017) and Jensen et al. (2023) shows that its mechanisms - retweets, mentions, hashtags - produce polarised and densely connected conversational architectures. In this context, bots are not simply external disruptors, but actors that strategically insert themselves into the platform's relational structures: coordinated amplification, temporal synchronisation, saturation of interactions, selective targeting of users or thematic groups. They thus participate in the mechanisms described by

Woolley & Howard (2018) under the term ‘computational propaganda,’ where manipulation relies less on the content itself than on the collective dynamics of exposure and visibility.

Faced with this complexity, traditional detection approaches-based on metadata, behavioural irregularities, or posting frequency-reach their limits. Probabilistic models such as Botometer (

Varol et al., 2017) can estimate the degree of automation, but their opacity, context dependency and fragility in the face of discreet botnets reduce their relevance (

Pacheco et al., 2020). These developments call for a renewal of detection frameworks by further integrating relational and interactional dimensions.

It is in this context that a socio-relational approach to detection appears essential. Rooted in the sociology of interaction (

Sacks, Schegloff & Jefferson, 1974;

Heritage, 1984,

2018), it considers that an actor's identity is manifested in the way they occupy relational space: turn-taking, contingency, mutual adjustment, distribution of commitments. Bots have characteristic limitations in these dimensions: repeated self-reactions, programmatic synchronisations, interactional rigidity, mechanical targeting, or lack of sequential negotiation. These ‘interactional anomalies’ are particularly relevant indicators that are still underutilised in computational detection.

The study presented in this chapter is part of this approach. Based on a corpus of 55,315,877 tweets collected as part of the ANR Beelzebot project

1, it examines three levels of interactional dynamics-self-interaction, internal interactions between accounts of interest, and external interactions with external accounts-in order to identify socio-relational configurations that can be transformed into explainable indicators for training AI models. The objective is not to analyse content or discursive strategies, but to characterise the forms of relational inscription that distinguish bots from human users.

Two questions guide this work: a) How do bots structure their social interactions at different levels? and b) How can these characteristics be transformed into indicators that can be used to train an AI model geared towards explainability?

2. State of the art

Digital social networks are now essential socio-technical infrastructures, in which information, expression and socialisation are deployed in ways that profoundly redefine opinion formation, visibility dynamics and the public experience of controversy. Far from being mere tools for interpersonal communication, these platforms generate environments regulated by algorithms that prioritise, filter and distribute content. They thus produce what some authors describe as an “algorithmic condition” of social life, marked by information asymmetries, fragmented attention regimes and new forms of polarisation. Contemporary transformations in the media ecosystem can be explained in part by the growing role of social networks in everyday information practices: more and more users are accessing news via their networks, subscriptions or platform recommendations (Pew Research Centre). This evolution is accompanied by an increase in vulnerabilities to informational disruptions defined by

Wardle & Derakhshan (2017): misinformation, disinformation, malinformation. Echo chambers, filter bubbles and algorithmic recommendation systems facilitate the circulation and crystallisation of these disruptions, creating environments where collective representations become fragmented (

Brachotte, 2025).

In this context, social network X, as a platform geared towards real-time information, is one of the most emblematic examples of these dynamics. Its technical structure – hashtags, retweets, mentions – organises the circulation of content into highly polarised conversational modules (

Himelboim et al., 2017) and promotes the formation of community networks that amplify controversies (Jensen et al., 2023). These properties make it a platform that is particularly vulnerable to computational manipulation strategies.

Social bots are thus emerging as key players. Defined by

Yang et al. (2022) as agents capable of producing programmed interactions, they are present in significant numbers (

Varol et al., 2017). Their increasing realism – reinforced by generative AI (

Najari et al., 2024) – makes them increasingly difficult to detect. Bots are not only involved in the automated dissemination of content, but also in modulating perceptions, artificially building consensus, and amplifying socio-political controversies (

Ferrara, 2020;

Grinberg et al., 2019). They thus introduce a computational dimension into the dynamics of the public sphere. Early detection approaches relied primarily on engineering features describing individual behaviours.

Ferrara et al. (2016) and

Varol et al. (2017) proposed models incorporating hundreds of parameters: publication frequencies, circadian rhythms, API metadata, and linguistic characteristics. These tools, such as Botometer, have enabled significant advances but have several limitations: difficulty in transferring between linguistic contexts, opacity of the scores produced, sensitivity to camouflage strategies, and vulnerability to adaptive bots. More recent work has encouraged the development of hybrid approaches combining behavioural, linguistic and structural signals. Neural models (

Cimino & Dell'Orletta, 2019;

Sallah et al., 2024) have improved performance but increased the difficulty of interpretation. Graph-based approaches (

Kalameyets, 2021) have renewed the perspective by highlighting the importance of relational structures: asymmetries, abnormal densities, coordination patterns, temporal co-activations. Graph neural networks (

Zeng et al., 2025) now make it possible to model these relationships in a detailed and multi-scale manner.

The BotPercent approach (

Tan et al., 2023) illustrates the maturity of these models by estimating the proportion of bots in a community rather than simply classifying individual accounts. A major turning point concerns the requirement for explainability. The work of

Doshi-Velez & Kim (2017) and

Mittelstadt et al. (2019) has shown that automated detection must now meet requirements for transparency, accountability and auditability. Explanatory tools (attention analysis, SHAP) represent progress but remain focused on individual decisions. What is still lacking, and is the subject of this chapter, is an approach capable of making explicit the socio-relational dynamics characteristic of botnets: self-amplification, synchronisation, co-targeting, mechanical interactions.

From this perspective, considering bots as interactive actors rather than technical anomalies constitutes a major theoretical shift. Their relational practices – self-interaction, internal coordination, external strategies – leave distinctive signatures that are difficult to imitate and particularly relevant for detection systems. Our contribution, which is still exploratory at this stage, is based on this link between social sciences and AI

2.

3. Methodology

We first relied on a corpus from the ANR Beelzebot project, comprising 55,315,877 French-language tweets related to COVID-19, collected between 1 December 2020 and 30 October 2021.

To identify accounts potentially operated automatically, we applied a set of individual criteria defined by the Beelzebot team (Brachotte et al.), consistent with account-feature-based approaches described notably by Ferrara et al. (2014). These criteria include, among others, the structure of the username, the temporal regularity of posts, and their dissemination speed.

We then compared these initial results with Botometer scores and verified the continued presence of these accounts on the X platform. At the end of this process, 851 accounts were identified as potentially automated.

These accounts were then subjected to an analysis of their interaction relationships with the aim of detecting relational configurations that may constitute relevant signals for future automated detection.

In this article, we focus on a socio-relational analysis based on a three-step protocol:

• identification of self-interaction patterns;

• examination of internal interactions between suspected accounts;

• analysis of their external interactions with accounts not included on the suspect list.

This study aims to make bot detection models more relational by integrating interaction analysis into the construction of indicators. Our detection model aims to include a qualitative output rather than relying solely on a quantitative score. The scientific objective is to lay the groundwork for an AI model that is more transparent, explainable, and better adapted to the relational dynamics that characterize botnets.

4. Results

4.1 Self-Interaction

4.1.1 Network Structure Analysis

We define self-interaction as any action through which an account engages with its own content, whether by self-mention, self-retweet, self-quote, or self-reply. Within the analysed dataset, 851 accounts were identified as potentially automated. Among them, 146 accounts (17%) performed at least one form of self-interaction, totalling 1,142 events. These interactions were distributed as follows: 26% self-retweets, 48% self-replies, 22% self-mentions, and 4% self-quotes.

From a relational standpoint, this pattern suggests that self-interaction functions not merely as a technical artefact but as a strategic operational mechanism. Self-replies, which constitute nearly half of all instances, are particularly salient: they simulate dialogic activity, generate superficial conversational depth, and artificially densify the interactional environment surrounding the account. Similarly, self-retweets and self-mentions operate as visibility-enhancing devices, increasing the probability that the account’s content is reintroduced into algorithmic circulation loops.

Interpreted through the lens of interaction sociology and Goffman’s (1959) impression management, these behaviours can be understood as deliberate attempts to construct an appearance of social embeddedness. By interacting with themselves, bots generate sign-vehicles that mimic the relational cues ordinarily associated with human presence-responsiveness, engagement, and continuity of activity. These signals contribute to an illusion of legitimacy while simultaneously reinforcing the account’s algorithmic footprint. Self-interaction, therefore, is not a marginal anomaly but a functional component of bot activity, enabling automated accounts to sustain a minimal interactional ecology and to integrate more effectively into the surrounding informational environment.

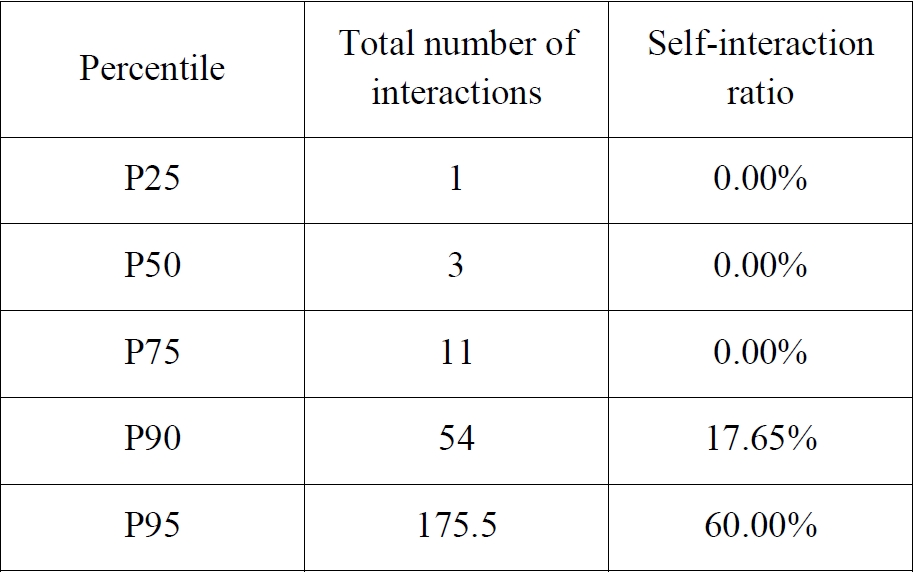

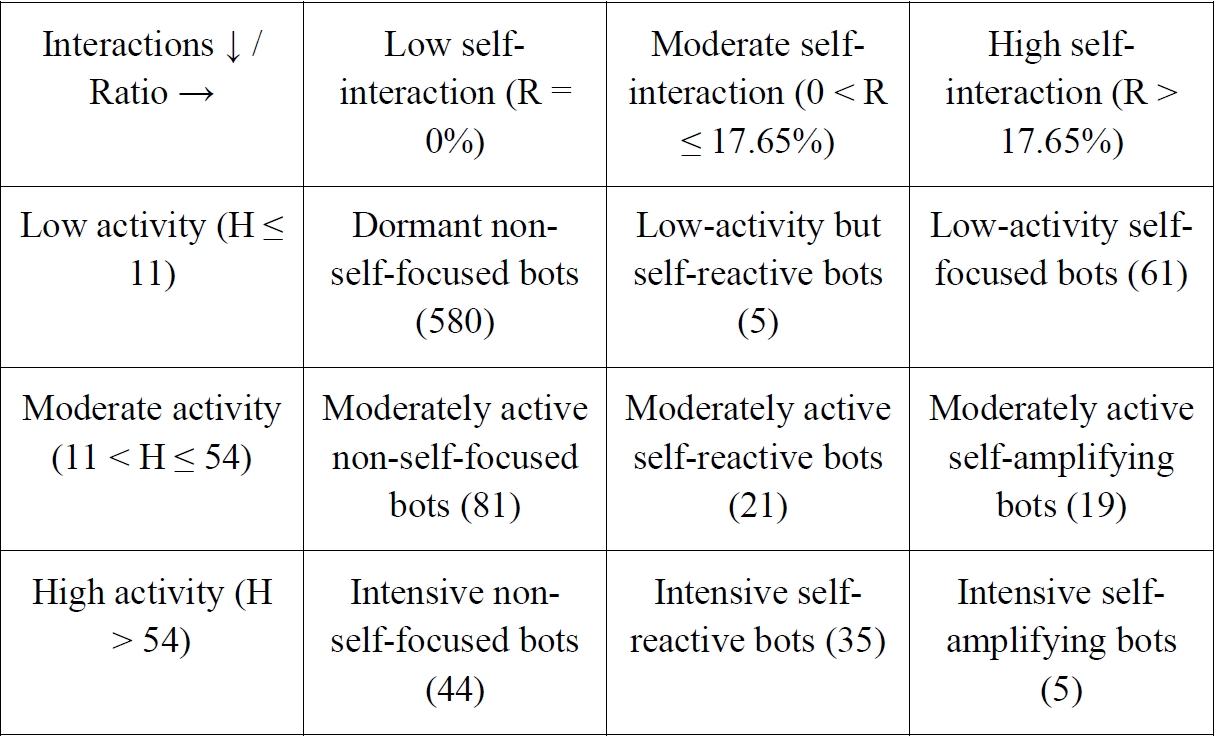

4.1.2 Classification of Automated Accounts in the Network

The distribution of accounts exhibiting self-interactions is highly asymmetric: while a majority of accounts display no self-interaction at all, a minority engage in intensive self-directed activity. In order to capture this heterogeneity, we relied on a percentile-based classification derived from two variables: 1) the total number of interactions produced by each account (H), and 2) the ratio of self-interactions relative to the total number of interactions (R). Percentiles indicate the value below which a given proportion of observations falls (

Hyndman & Fan, 1996). This nonparametric approach is particularly well suited to asymmetric and heavy-tailed distributions, as it avoids assumptions of normality and preserves the empirical structure of interactional behaviours.

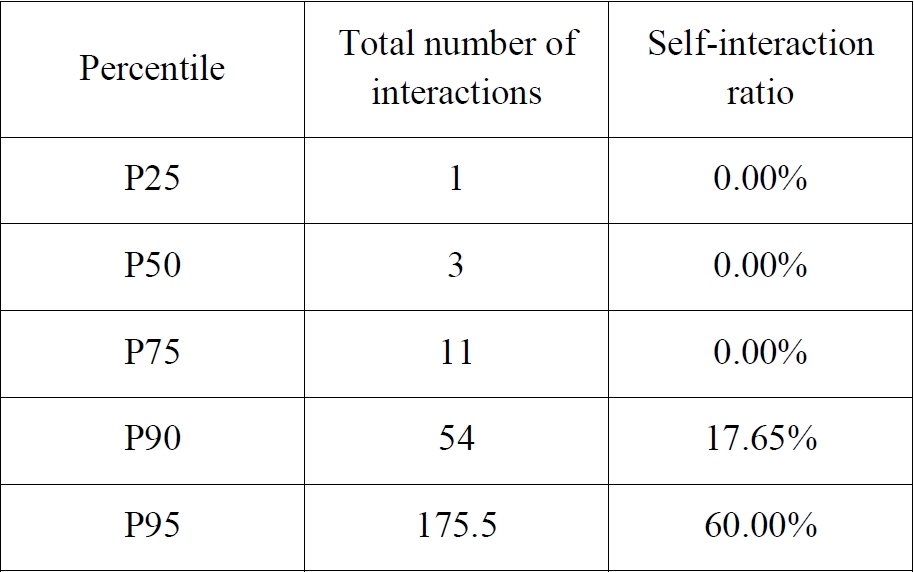

The percentile thresholds obtained are shown below:

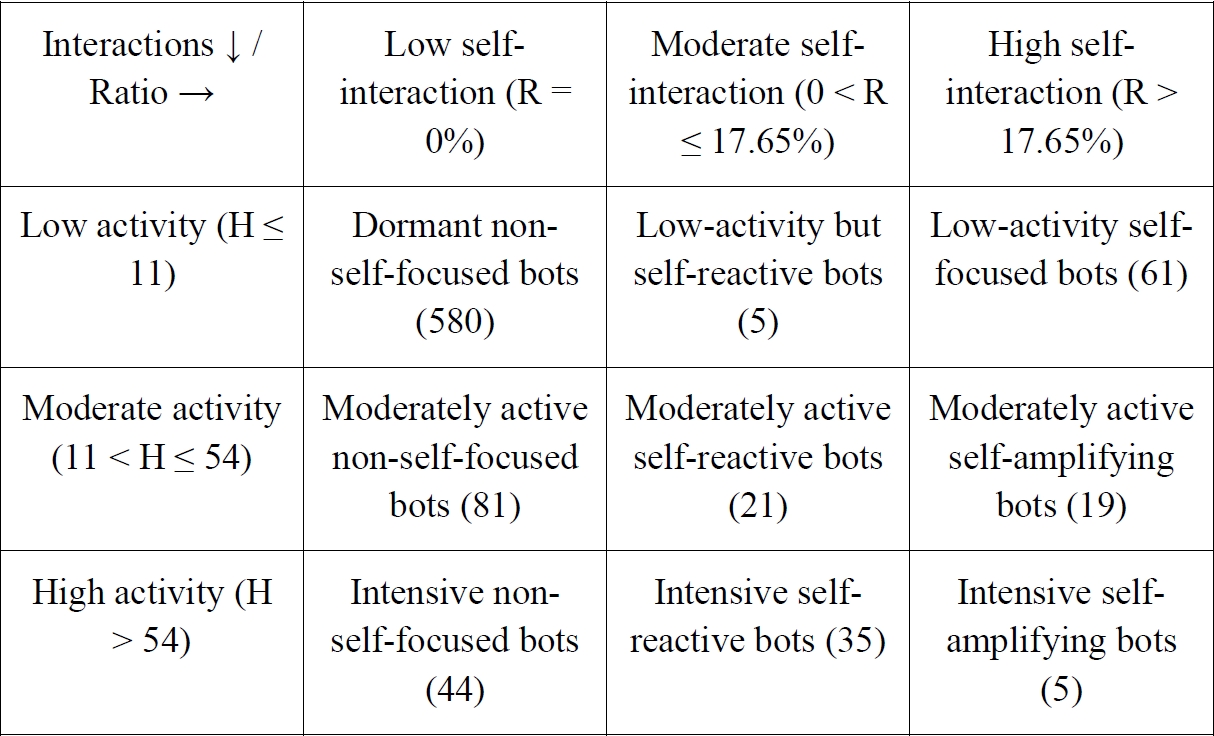

Based on these thresholds, we constructed a segmentation matrix distinguishing nine behavioural profiles according to activity level (

H) and self-interaction intensity (

R):

This segmentation highlights the diversity of automated interactional strategies. The largest group consists of dormant non-self-focused bots (580 accounts), which exhibit minimal activity and no detectable self-interaction. These bots likely represent low-maintenance or residual automated accounts. A second set comprises 80 accounts combining low or moderate activity with non-negligible use of self-interaction. Such behaviour may reflect targeted strategies of self-promotion, visibility reinforcement, or manipulated engagement-bot behaviours designed to artificially increase perceived presence without producing substantial outward activity.

Finally, a small but analytically significant group of five intensive self-amplifying bots combines very high overall activity with an exceptionally elevated self-interaction ratio. These accounts constitute the most aggressive operational profiles: they repeatedly react to their own content, generating dense and persistent loops of artificial engagement that maximise their algorithmic footprint. By deriving these categories from percentile-based thresholds, we establish a robust empirical foundation for the qualitative classification of bot profiles, providing interpretable features suitable for the training of an explainable AI model.

4.2 Internal Interactions

In this section, we analyse the interactional dynamics occurring within the set of 851 suspected accounts by distinguishing two complementary dimensions. : 1) Explicit interactions, referring to direct relational actions-mentions, retweets, replies, or quotes-through which one account publicly addresses or amplifies another, and 2) Implicit interactions, defined as coordinated behaviours such as the shared use of identical hashtags or links within a given temporal window, which reveal patterns of alignment or co-activation without requiring direct mutual addressing.

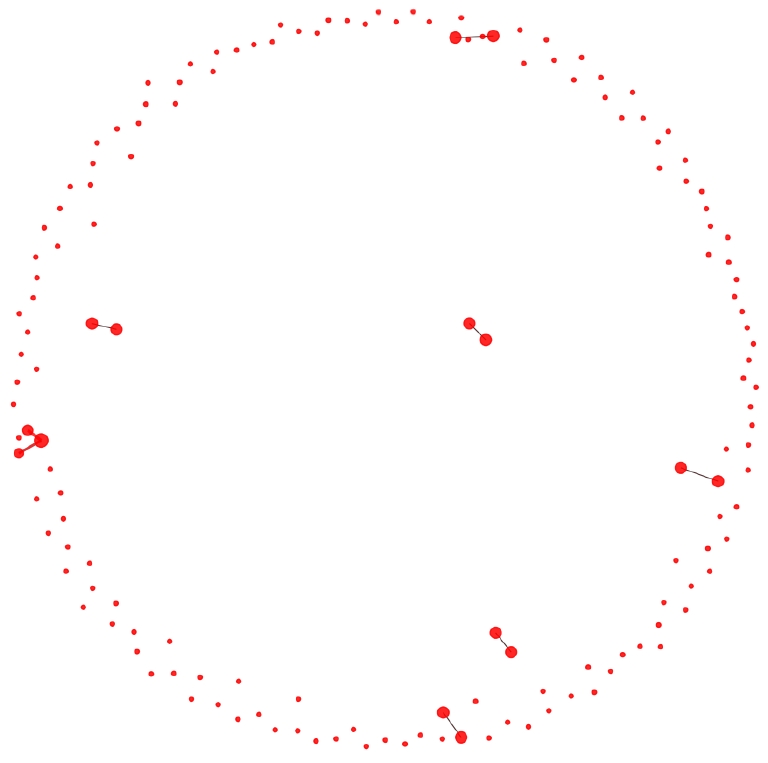

4.2.1 Explicit Interactions

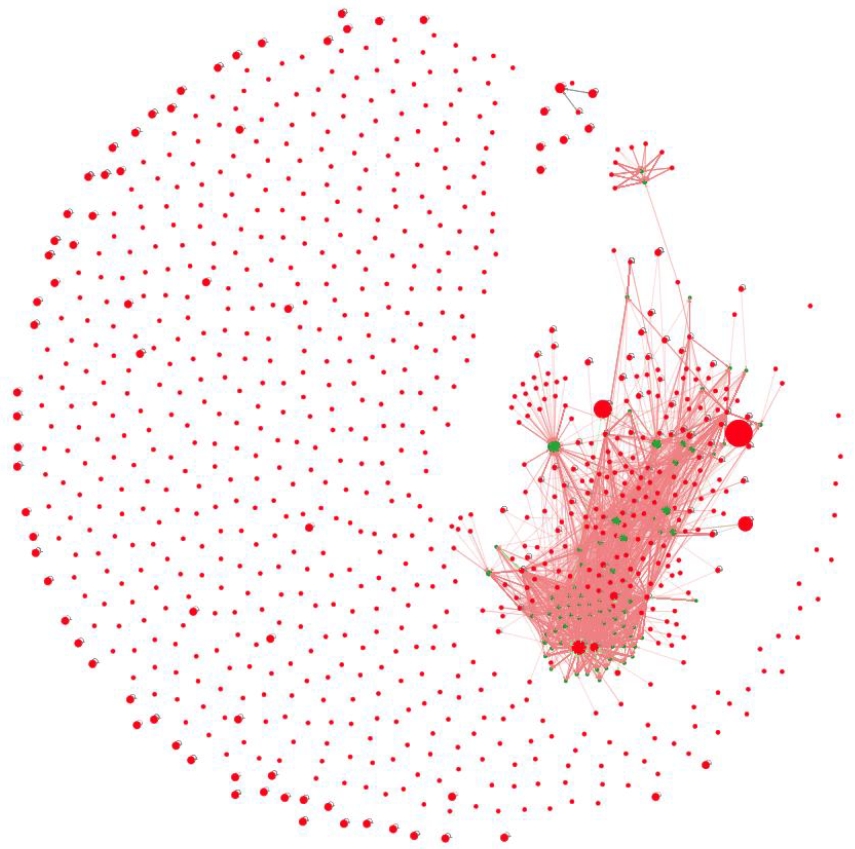

The network visualisation below represents explicit interactions among the suspected accounts. Each node corresponds to an individual account, and each directed edge indicates the presence of an interaction. Node centrality is encoded through PageRank scores, such that more influential or structurally prominent accounts appear proportionally enlarged. The colour and thickness of the edges illustrate interactional intensity: thin, dark edges correspond to infrequent or sporadic exchanges, whereas thick, red edges signal recurrent or sustained interactions. This representation highlights the emergence of localised hubs and tightly connected subgroups, suggesting differentiated levels of engagement and potential coordination patterns within the network.

4.2.2 Implicit Interactions

To complement the analysis of explicit exchanges, we examined implicit interactions, defined as the joint use of identical content items within short time intervals. Such interactions do not require direct addressing between accounts, yet they reveal coordinated behavioural patterns: simultaneous use of specific hashtags, repetition of the same URLs, or publication of closely aligned messages within narrow time windows. These forms of synchronised content production are particularly relevant for bot analysis, as they may signal underlying organisational structures, shared automation scripts, or alignment around common amplification objectives.

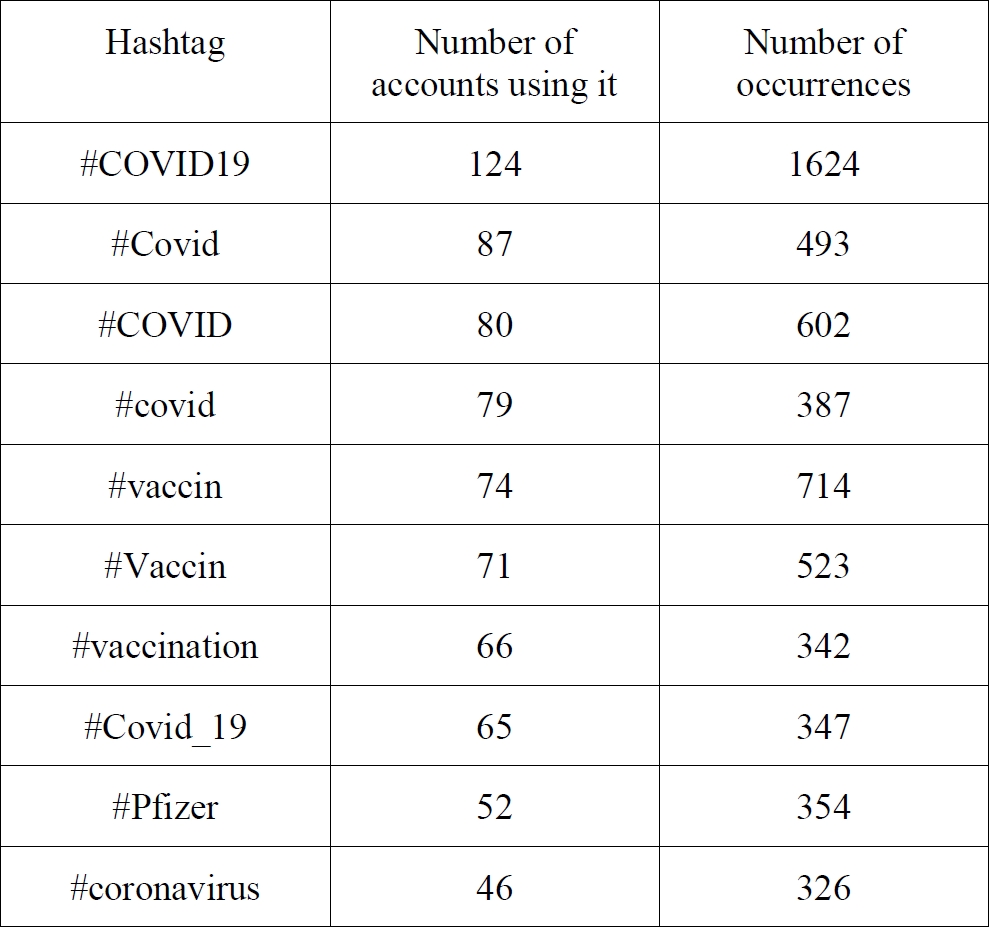

4.2.2.1. Identical Hashtags

Within the set of 851 suspected accounts, we identified 1,481 hashtags that were used by at least two accounts. The table below presents the ten hashtags most frequently shared across the accounts:

Although these hashtags appear frequently across the accounts, their relevance for detecting coordinated behaviour is limited by their general popularity during the pandemic period. High-frequency hashtags associated with large-scale events (e.g., #COVID19, #vaccin) naturally generate substantial organic activity, making isolated frequency counts insufficient to infer coordination.

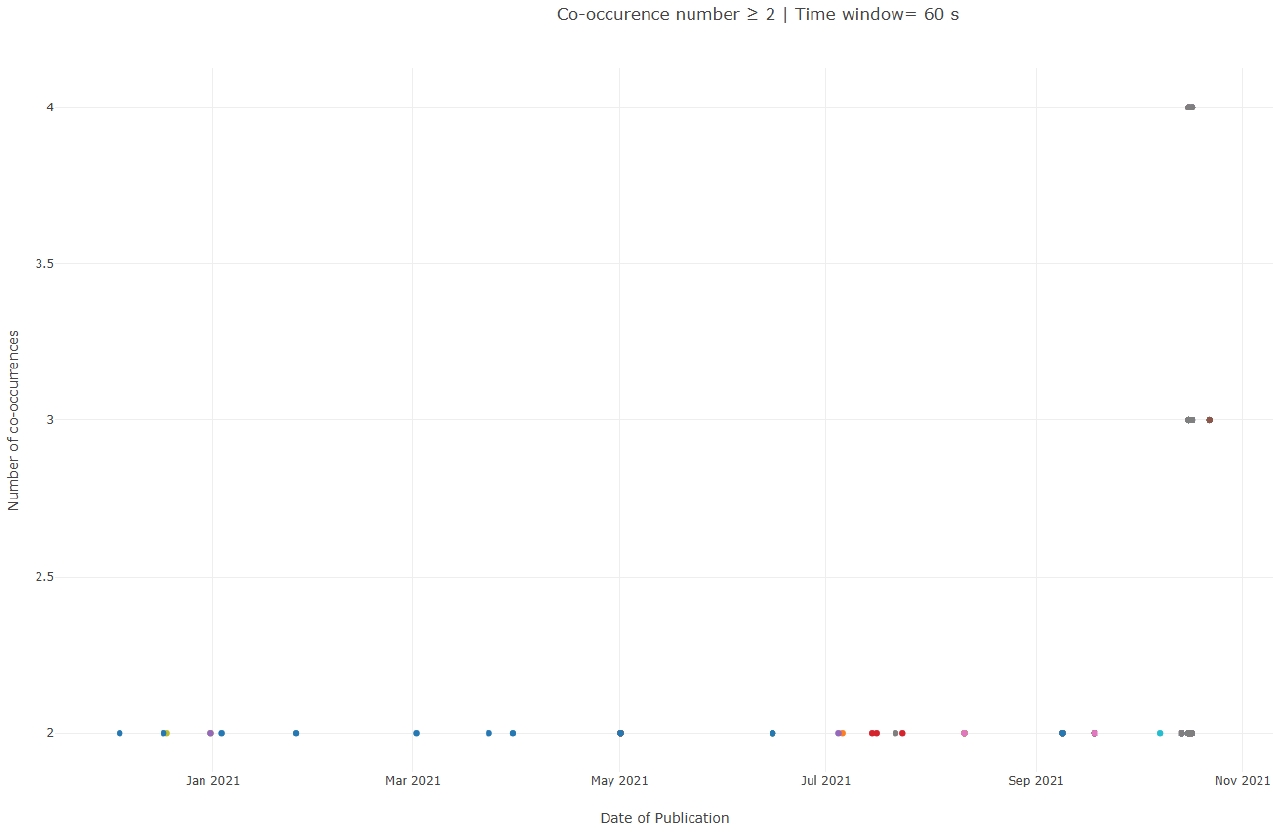

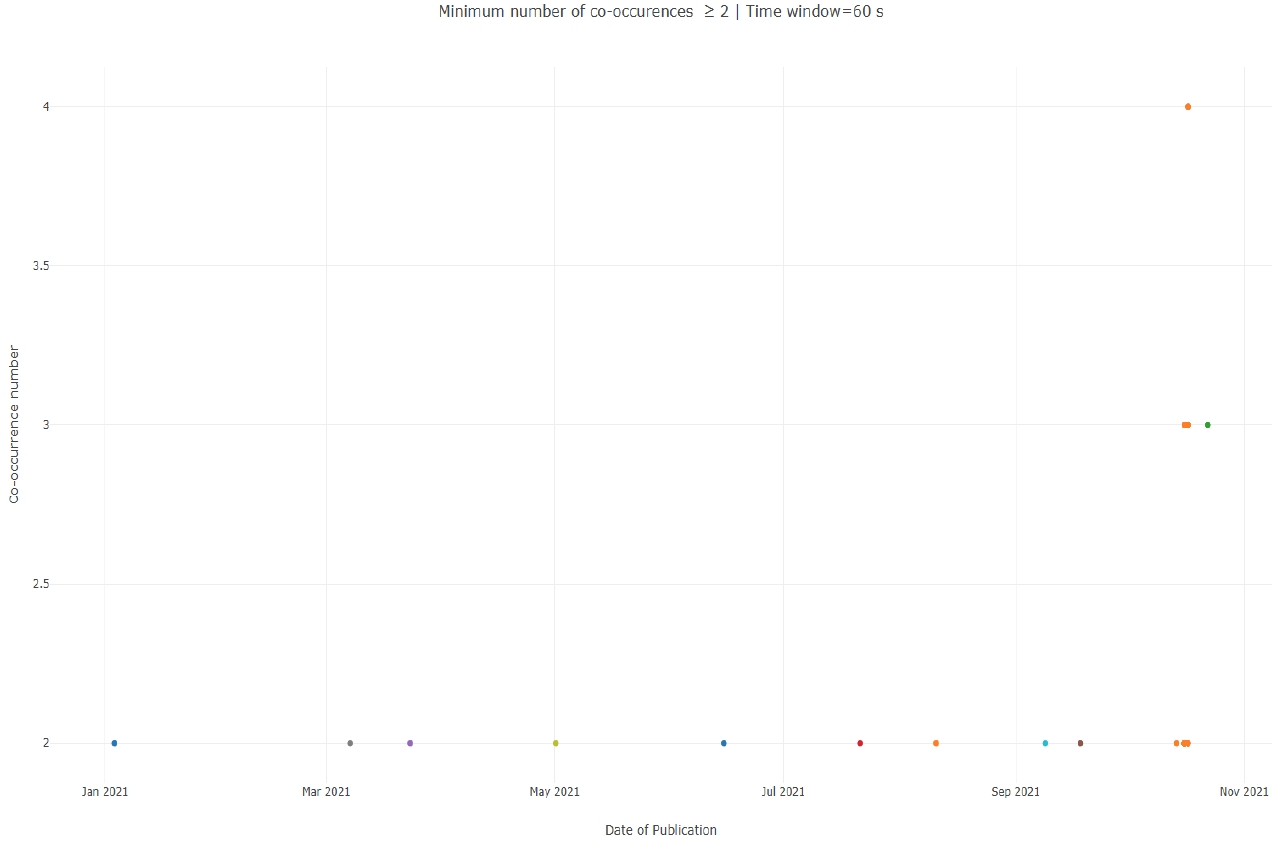

To address this limitation and refine the analysis, we examined whether posts containing the same hashtags were published within identical or closely adjacent temporal windows, specifically within a 60-second interval. Posts appearing in such constrained timeframes provide stronger evidence of synchronised activation, which may reflect automation scripts, shared posting schedules, or common triggers that orchestrate behaviour across multiple accounts. This temporal dimension is therefore essential for distinguishing mere thematic convergence from coordinated operational patterns.

Initial results indicate that a subset of hashtags is used in a temporally coordinated manner:

• 23 hashtags were used synchronously by pairs of accounts,

• 3 hashtags were used synchronously by trios,

• 2 hashtags were activated within the same interval by groups of four accounts.

Although these clusters remain limited in size, the presence of repeated short-window co-activations suggests localised coordination patterns that cannot be explained solely by trending-topic dynamics.

4.2.2.2. Identical Links

Beyond hashtags, we examined the co-use of URLs-another potential indicator of implicit coordination, as links often function as mobilisation vectors within computational propaganda strategies. Across the 851 suspected accounts, 732 distinct links were used by at least two accounts.

As with hashtags, we assessed whether these links were published within the same 60-second window in order to detect synchronised activation. The temporal analysis revealed:

These patterns of link co-use, though relatively sparse, are analytically significant. URL sharing is generally less frequent and less uniform than hashtag usage, which means that even small synchronised clusters may indicate the presence of shared automation scripts or aligned operational routines. When combined with explicit interactions and hashtag synchronisation, these findings contribute to the identification of multi-layered coordination behaviours within bot networks.

4.2.3. Interim Assessment

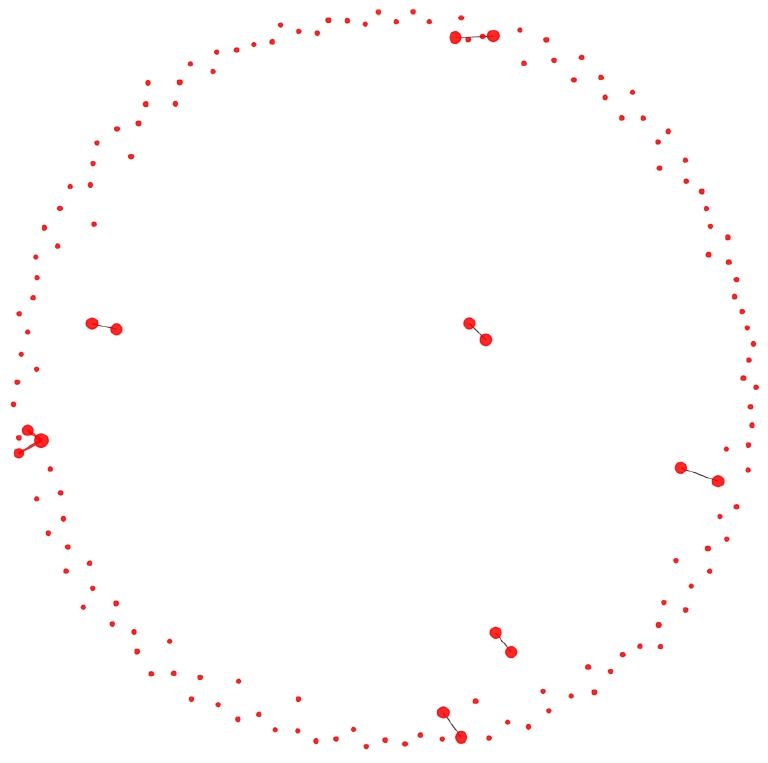

The analysis of internal interactions indicates that the 851 suspected accounts exhibit the structural properties of a low-connectivity botnet, characterised by a marked reduction in explicit relational ties. Very few direct mentions, replies, retweets, or quotes circulate within the group, suggesting that these accounts avoid forming visible social clusters. Such minimal explicit linkage is consistent with botnets designed to remain covert within the broader interactional landscape.

Despite this low relational density, the accounts display clear patterns of behavioural coordination. Across the dataset, 1,481 hashtags and 732 URLs were co-used by at least two accounts, and temporal analysis revealed synchronised activation (within ≤ 60 seconds) for 28 hashtags and 16 links. These micro-episodes of synchronisation correspond to the phenomenon described by

Pacheco et al. (2020) as implicit coordination, in which near-simultaneous publication of identical content generates artificial micro-peaks of activity intended to modulate algorithmic signals rather than engage in social interaction.

The predominance of highly popular hashtags-particularly those related to COVID-19-suggests an opportunistic insertion strategy, whereby automated accounts embed themselves within high-volume, high-noise information streams. This strategy enhances camouflage: by operating in densely populated conversational spaces, their contributions become more difficult to distinguish from surrounding organic activity. Temporal synchronisation strengthens this effect, producing bursts of aligned activity that mimic the emergent rhythms typical of collective human engagement.

Taken together, these findings point to a behaviourally coordinated botnet, whose operations rely more on content co-activation and timing alignment than on explicit relational ties. This configuration is characteristic of systems designed to intervene discretely within information flows-amplifying, reinforcing, or modulating visibility-without establishing detectable social connections between accounts. It reflects a mode of automation that privileges algorithmic influenceover social positioning, consistent with contemporary low-connectivity botnet architectures.

4.3 External Interactions

We define external interactions as any action (tweet, reply, quote, retweet) whereby an account in the corpus interacts with another account not included in the list of suspected accounts. These external accounts may potentially correspond to human users.

We define external interactions as any action-tweet, reply, quote, or retweet-through which an account in our corpus engages with an account outside the set of 851 suspected accounts. These external targets may correspond to human users or to non-suspect automated accounts, and therefore constitute an important analytical dimension: they reveal how suspected bots position themselves within the broader interactional environment. Whereas internal interactions capture the relational architecture of the botnet itself, external interactions provide insight into its modes of insertion, visibility strategies, and potential influence on surrounding conversational spaces.

4.3.1. Network Structure Analysis

Within the sample of 851 suspected accounts, 682 accounts (80%) engage in at least one interaction with an external account, and 563 of them interact exclusively with external accounts. This configuration suggests that a substantial proportion of suspected automated accounts orient their activity outward, targeting accounts that are potentially human. Whereas internal interactions inform us about the organisation of relations within the botnet, external interactions reveal how these accounts insert themselves into the wider conversational space.

Across all suspected accounts, we identify 47,362 external interactions, distributed as follows:

• 50% retweets,

• 2% replies,

• 36% mentions,

• 12% quotes.

The predominance of retweets (50%) indicates a communicative strategy centred on amplification rather than content generation. From a network sociology perspective, this reliance on retweeting can be interpreted as the tactical mobilisation of weak ties as vectors of diffusion (

Granovetter, 1973). Retweets enable automated accounts to participate in ongoing conversations, increase their visibility, and reinforce selected messages while incurring minimal interactional cost-thus avoiding the obligations associated with direct conversational engagement, such as replying or negotiating meaning.

Mentions and quotes, which together account for 48% of external interactions, reveal complementary strategies of insertion. Mentions provide a mechanism for targeted visibility, directing automated activity toward specific accounts and increasing the likelihood of reciprocal exposure. Quotes, although less frequent, perform a dual function: they replicate content while adding a thin layer of contextualisation, thereby simulating interpretive agency without requiring substantive discursive contribution.

Taken together, the distribution of external interaction types portrays a model of activity in which bots privilege low-commitment, high-diffusion practices, enabling them to affect information flows without engaging in socially demanding forms of interaction.

4.3.2. Classification of Automated Accounts in the Network

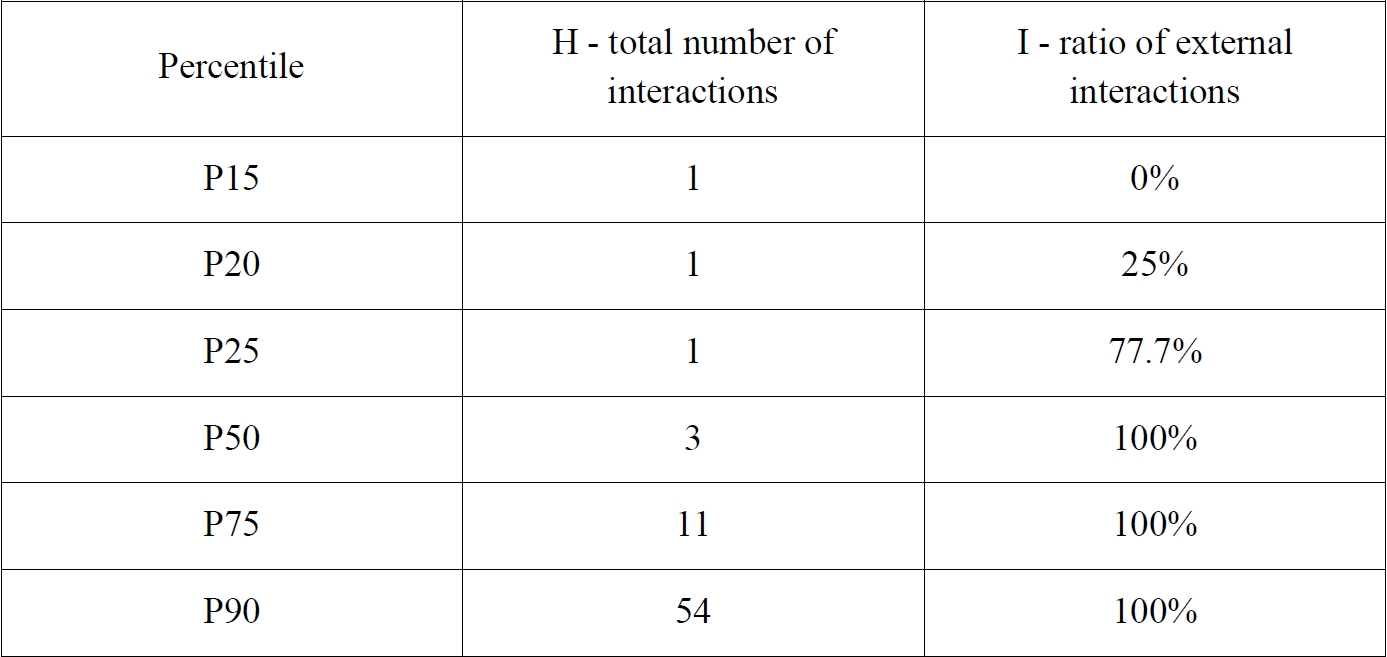

Using the same methodological framework applied to self-interaction, we classify suspected accounts according to two indicators: 1) the total number of interactions produced by each account (H), and 2) the ratio of external interactions relative to all interactions (I).

Given the asymmetric distribution of the data, we again rely on percentiles (

Hyndman & Fan, 1996) to derive empirical thresholds. The table below presents the relevant percentile values:

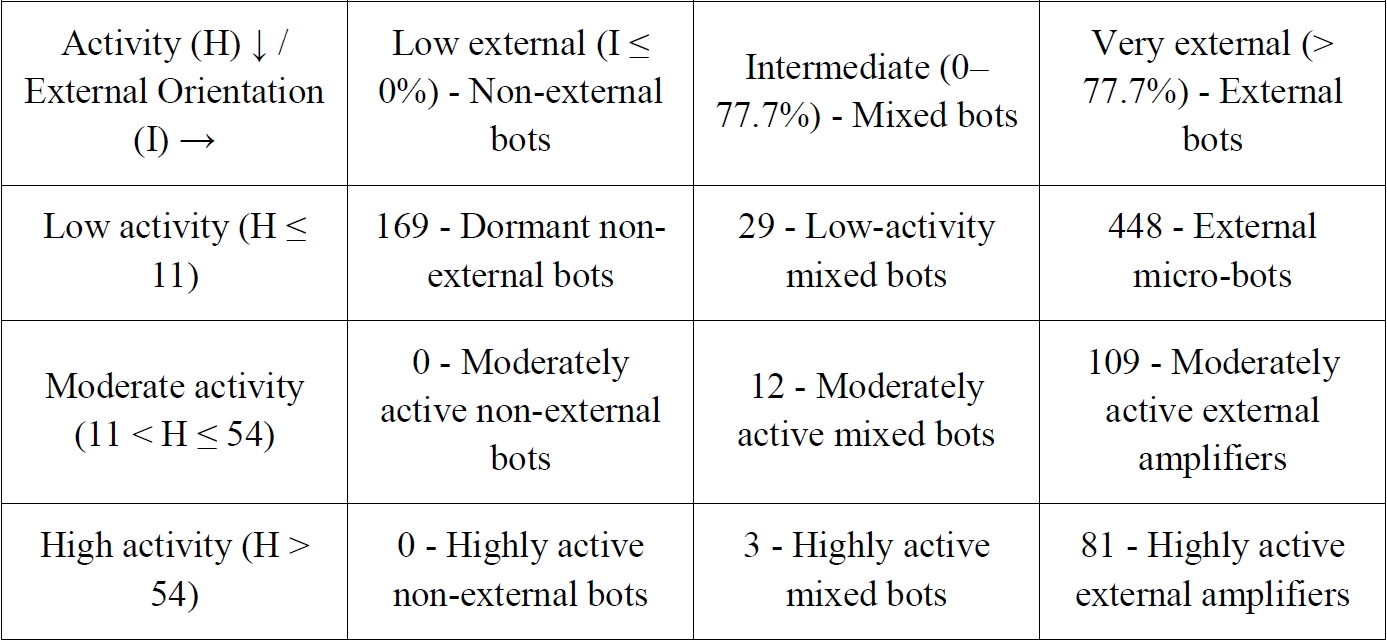

On this basis, we construct a 3×3 segmentation matrix distinguishing accounts by their level of activity (

H) and their degree of external orientation (

I):

This typology offers a qualitative refinement beyond the assignment of a simple automation score. It enables:

• a more precise understanding of the functional role played by each bot within the interactional ecosystem (e.g., amplifiers vs. micro-bots),

• a more detailed structural characterisation of the botnet, revealing how automated accounts distribute their efforts between internal cohesion and external projection,

• the identification of operational subgroups, such as external micro-bots whose activity is sparse but almost exclusively outward-facing, mixed bots combining internal and external interactions, or external amplifiers whose high activity concentrates on outward-oriented engagement.

By grounding these categories in empirical percentiles, this approach provides a robust and interpretable framework for integrating qualitative behavioural labels into an explainable AI model. It thus supports a bot detection methodology that is attentive not only to degrees of automation but also to interactional roles and strategies.

4.3.3. Co-targeting

In addition to quantitative indicators, we conducted a qualitative analysis to determine whether suspected accounts systematically targeted the same external actors. This approach allows us to assess whether automated accounts converge toward common interlocutors, thereby revealing potential alignment strategies or coordinated attempts to influence specific nodes within the wider information ecosystem.

The network visualisation above represents directed interactions between suspected automated accounts and the external accounts they address most frequently. Each node corresponds to an account, with automated accounts displayed in red and external accounts in green. Node size is proportional to structural centrality, as measured by PageRank, which increases when a node receives interactions from influential accounts. Edges are colour-coded to indicate the direction of interaction: light red edges represent actions from suspected bots toward external accounts, while light green edges represent interactions in the opposite direction.

The analysis identifies 2,787 external accounts that were addressed by at least two suspected accounts. Examination of the ten most frequently targeted accounts reveals a marked concentration on highly visible media organisations, prominent institutional or political actors, and influential public commentators. This pattern suggests a strategy aimed at maximising the reach and embedding of bot interventions within prominent public discussions, leveraging the visibility of influential nodes as amplifiers. By repeatedly addressing the same high-centrality targets, these accounts increase the likelihood that their messages will be integrated into broader information flows or will appear as part of trending conversational streams.

From a socio-technical perspective, this form of co-targeting corresponds to a visibility-seeking strategy, whereby automated accounts exploit the symbolic and algorithmic weight of central actors. Rather than engaging in dispersed or conversationally meaningful interactions, the botnet appears to orient its efforts toward nodes capable of redistributing attention. This behaviour aligns with models of computational propaganda in which influence is exerted less through persuasion than through strategic insertion into pre-existing high-visibility circuits.

4.3.4. AI Perspectives

The network analysed here presents a form of coordination that is both operationally structured and intentionally discreet, enabling it to evade detection models that rely primarily on explicit relational links. The botnet combines several functional profiles:

1) self-amplification, whereby accounts reinforce their own content through self-directed interactions;

2) external amplification, through frequent interactions with potentially human accounts-particularly highly visible ones; and

3) implicit coordination, through the co-diffusion of hashtags and URLs within narrowly shared temporal windows.

Taken together, these behaviours describe a botnet whose organising principle is informational impact rather than internal connectivity.

The methodological challenge is to convert these empirical observations into interpretable indicators suitable for integration into future AI models. Rather than producing a binary decision (“botnet or not?”) or a probabilistic score, our objective is to move toward an explainable and relational model capable of identifying how and why an account contributes to coordinated automated activity. The present analysis constitutes an exploratory phase aimed at calibrating such an approach before applying it to additional corpora.

From this perspective, integrating multi-level interactional dynamics is essential. By examining three relational strata-self-interaction, internal implicit/explicit interactions, and external interactions-we demonstrate that automated networks generate distinctive relational signatures. These signatures constitute interpretable features that can be operationalised in a learning framework, allowing the model to capture not only the behaviour of individual accounts but their systemic role within a coordinated ensemble.

We also propose criteria for identifying a coordinated yet discreet botnet, characterised by:

• the absence of explicit internal ties,

• the co-use of hashtags and links, and temporal synchronisation among multiple accounts. This approach seeks not merely to label accounts individually but to reveal the functional roles they occupy within the broader automated structure.

Based on our corpus, we identify two promising thresholds for future exploration in AI modelling:

Intensive self-amplifying bots: total number of interactions > 54; self-interaction ratio > 17.65%.

Active external amplifying bots: total number of interactions > 54; external interaction ratio > 77.7%.

These thresholds offer an initial foundation for constructing a relational detection model built on interpretable, transferable, and behaviourally grounded indicators. Such a model would move beyond probability-based classification and toward a finer-grained understanding of automated ecosystems and their operational strategies. These criteria provide an initial basis for building a more relational detection model based on interpretable and transferable behavioral indicators.

5. Conclusion, limitations and perspectives

This exploratory study set out to analyse the interactional dynamics of accounts suspected of automation, with the aim of establishing the foundations for data processing within the development of an artificial intelligence model dedicated to their detection. Drawing on the theoretical contributions presented in the introduction and state of the art-particularly the notions of sociotechnical agency, implicit coordination, and relational signatures-we argue that bots cannot be understood solely through individual behavioural markers. They must be examined within the interactional and systemic configurations through which they operate.

The analysis of self-interactions, internal explicit and implicit interactions, and external interactions reveals a botnet architecture that is both coordinated and deliberately discreet. Rather than relying on internal connectivity, it is structured around strategies of behavioural synchronisation, content co-activation, and strategic insertion into high-visibility informational flows. This configuration is consistent with recent descriptions of low-connectivity botnets and computational propaganda infrastructures, which prioritise informational impact over social cohesion. The identified patterns-self-amplification loops, targeted amplification of highly visible external accounts, co-use of hashtags and URLs within shared temporal windows-constitute distinctive relational signatures that extend and enrich existing approaches to automated account detection.

From this perspective, the study offers a significant contribution to AI research. The identified relational features provide a robust empirical and methodological foundation for training models capable not only of classifying automated accounts but of doing so through interpretable and explainable qualitative labels. By shifting from probabilistic scores to functional roles (e.g., intensive self-amplifying bots, external amplifiers, mixed bots), we move toward the development of relational detection models that capture the systemic nature of automated behaviour. Such models respond to the growing requirements for transparency, auditability, and explainability in AI-based decision systems.

These results also hold strategic importance for the ANR Beelzebot project. The project’s ambition is to move beyond traditional approaches based on isolated behavioural traces, and instead to construct tools that incorporate interactional patterns, sociotechnical structures, and distributed coordination mechanisms. The typologies, thresholds, and indicators proposed in this study therefore constitute a foundational building block for defining relational features to be used in the supervised learning models and hybrid analytical frameworks envisioned in Beelzebot. They also provide a conceptual grounding that bridges computational analysis with the theoretical frameworks of the humanities and social sciences, thereby strengthening the interdisciplinary dimension of the project.

Several limitations must nevertheless be acknowledged. First, the study does not include a linguistic or semantic analysis of the published content, which would enhance our understanding of discursive coordination strategies and potential narrative alignments. Second, the presence of many low-activity accounts among the 851 examined profiles requires qualitative, account-by-account verification to better distinguish marginally active human users from lightly scripted bots. Finally, the typologies and percentile-based thresholds proposed here remain preliminary: their robustness and transferability must be assessed on additional corpora, across languages and temporal contexts, in order to ensure their validity within a generalisable AI model.

Despite these limitations, this research opens important perspectives for the development of more transparent, more responsible, and more trustworthy AI systems. Beyond explainability, it highlights the necessity of reducing biases, improving robustness against adaptive bot behaviours, and upholding digital rights and ethical principles governing automated detection. By incorporating interactional dynamics and systemic roles, future models-including those developed within the Beelzebot framework-will be better equipped to capture the complexity of contemporary botnets and to contribute to the preservation of information integrity within increasingly algorithmically mediated public spaces.

Notes

Figure 1.

Figure 2.3×3 Segmentation Matrix Based on Percentiles

Figure 3.

Figure 4.Top 10 most used identical hashtags

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Figure 8.3×3 Segmentation Matrix Based on Percentiles

Figure 9.External Interactions Network Graph

REFERENCES

- Aljabri, M., Fakeeh, M., Meziane, F., & Al-Ohali, Y. (2023). Detecting malicious social bots: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys, 55, (10), 1-34.

- Bach, C. (2021). A usage-based construction grammar approach to discourse (Doctoral dissertation). Université Paris Nanterre.

- Bender, E. M., Gebru, T., McMillan-Major, A., & Shmitchell, S. (2021). On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big? In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency(pp. 610-623).

- Boyd, D. M., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13, (1), 210-230.

- Brachotte, G. (2025). Dans l’ombre des bots : comment les robots manipulent l’information sous X. In P. Lardellier (Dir.), Des clicks et des clashs : controverses et polémiques dans les réseaux socio-numériques. L’Harmattan.

- Bruns, A., & Highfield, T. (2016). Is Habermas on Twitter? Social media and the public sphere. In A. Bruns et al. (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Social Media and Politics (pp. 56-73). Routledge.

- Cimino, A., & Dell’Orletta, F. (2019). A hierarchical neural network approach for bots and gender profiling. In Notebook for PAN at CLEF 2019.

- Clark, J., Dinakar, K., & Jones, J. (2016). Linguistic features for bot detection. (Référence citée dans ton WP1..

- Croft, W. (2001). Radical Construction Grammar. Oxford University Press.

- Dehghan, A., Siuta, K., Skorupka, A., Dubey, A., Betlen, A., Miller, D., Xu, W., Kamiński, B., & Prałat, P. (2023). Detecting bots in social networks using node and structural embeddings. Journal of Big Data, 10, (119), 1-26.

- Doshi-Velez, F., & Kim, B. (2017). Towards a rigorous science of interpretable machine learning. arXiv, 1702.08608.

- Ellison, N. B., & Vitak, J. (2015). Social network site affordances and their relationship to social capital processes. In S. Sundar (Ed.), The Handbook of the Psychology of Communication Technology (pp. 205-227). Wiley.

- Ferrara, E. (2020). What types of COVID-19 conspiracies are populated by Twitter bots?. First Monday, 25(6.

- Ferrara, E., Varol, O., Davis, C., Menczer, F., & Flammini, A. (2016). The rise of social bots. Communications of the ACM, 59, (7), 96-104.

- Fillmore, C. J., Kay, P., & O’Connor, M. (1988). Regularity and idiomaticity in grammatical constructions. Language, 64, (3), 501-538.

- Fried, M. (2015). Construction Grammar. In E. Dąbrowska & D. Divjak (Eds.), Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics. De Gruyter.

- Giachanou, A., & Ghanem, B. (2019). Bot and gender detection using textual and stylistic information. Notebook for PAN at CLEF 2019.

- Gledhill, C., Patin, M., & Zimina, M. (2017). Construction Grammar and its Applications. Paris.

- Goffman, E. (2023). The presentation of self in everyday life. In Social theory re-wired (pp. 450-459). Routledge.

- Goldberg, A. E. (1995). Constructions: A Construction Grammar Approach to Argument Structure. University of Chicago Press.

- Goldberg, A. E. (2006). Constructions at Work: The Nature of Generalization in Language. Oxford University Press.

- Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360-1380.

- Grinberg, N., Joseph, K., Friedland, L., Swire-Thompson, B., & Lazer, D. (2019). Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Science, 363, (6425), 374-378.

- Hartmann, S., & Pleyer, M. (2016). Constructions in mind: A usage-based perspective on Construction Grammar. Linguistics Vanguard, 2, (1), 1-13.

- Heritage, J. (1984). Garfinkel and Ethnomethodology. Polity Press.

- Heritage, J. (2018). The Epistemics of Social Interaction. Routledge.

- Himelboim, I., Smith, M. A., Rainie, L., Shneiderman, B., & Espina, C. (2017). Classifying Twitter topic-networks using social network analysis. Social Media + Society, 3, (1.

- Hoffmann, T., & Trousdale, G. (2013). Construction Grammar: Introduction to the Theory. Oxford University Press.

- Hyndman, R. J., & Fan, Y. (1996). Sample quantiles in statistical packages. The American Statistician, 50, (4), 361-365.

- Ilias, L., Kazelidis, I. M., & Askounis, D. (2024). Multimodal detection of bots on X (Twitter) using transformers. IEEE Preprint.

- Ishfaq, R., Abid, M. K., Fuzail, M., Khan, T. F., Naeem, A., & Aslam, N. (2025). Utilizing deep learning and linguistic embeddings for Twitter bot identification. International Journal of Social Sciences Bulletin, 1, (1.

- Kalameyets, D. (2021). Graph-Based Techniques for Social Bot Detection (Doctoral dissertation).

- Kavadi, D. P., Sanaboina, C. S., Patan, R., & G, omi. (2022). N-gram-based machine learning approach for bot or human detection. In Proceedings of ISMSI 2022.

- Knauth, J. (2019). Language-agnostic Twitter bot detection. In Proceedings of RANLP 2019 (pp. 550-558).

- Lazer, D., Baum, M., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A., Greenhill, K., Menczer, F., & Zittrain, J. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359, (6380), 1094-1096.

- Lazer, D., Pentland, A., Adamic, L., Aral, S., Barabási, A.-L., Brewer, D., & Van Alstyne, M. (2009). Computational social science. Science, 323, (5915), 721-723.

- Michaelis, L. (2006). Construction Grammar. In K. Brown (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2nd ed.). Elsevier.

- Mittelstadt, B., Russell, C., & Wachter, S. (2019). Explaining explanations in AI. In Proceedings of FAT 2019.

- Najari, M., Brcic, M., & Tjoa, E. (2024). AI-generated disinformation and social bots. Journal of Cybersecurity.

- Pacheco, D., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2020). Uncovering coordinated networks on social media. arXiv. 2001.05658.

- Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking in conversation. Language, 50, (4), 696-735.

- Sallah, A., Abdellaoui Alaoui, E. A., Agoujil, S., Wani, M. A., Hammad, M., Abd El-Latif, A. A., & Maleh, Y. (2024). Fine-tuned understanding: Enhancing social bot detection with transformer-based classification. IEEE Access.

- Santos, B. L., Ferreira, G. E., Torres do Ó, M., Braz, R. R., & Digiampietri, L. A. (2022). Comparison of NLP techniques in social bot detection during Brazilian presidential elections. iSys - Revista Brasileira de Sistemas de Informação, 15, (1), 12:1-12:22.

- Tan, C., Tian, Z., Zhang, B., & Ma, J. (2023). BotPercent: Estimating bot populations in social media communities. arXiv, 2306.16710.

- Varol, O., Ferrara, E., Davis, C., Menczer, F., & Flammini, A. (2017). Online human-bot interactions: Detection, estimation, and characterization. In Proceedings of ICWSM 2017.

- Wardle, C., & Derakhshan, H. (2017). Information Disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policymaking. Council of Europe.

- We Are Social, & Meltwater. (2024). Digital 2024 Global Overview Report.

- We Are Social, & Meltwater. (2025). Digital 2025 Global Overview Report.

- Woolley, S. C., & Howard, P. N. (2018). Computational propaganda: Political parties, politicians, and political manipulation on social media. Oxford University Press.

- Yang, K.-C., Varol, O., Hui, P.-M., & Menczer, F. (2022). The digital influence machine: Social bots and the manipulation of public opinion. In K. Thorson & C. Wells (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Networked Communication. Oxford University Press.

- Zeng, J., Liu, Q., & Wang, Y. (2025). Emoji-driven semantic enhancement for robust bot detection. Journal of Information Security.

Figure & Data

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by