Abstract

The present paper aims at analyzing the so-called legal phrases, sometimes called collocations, expressions, or even idioms, which constitute one of the numerous terminological difficulties of legalese, and often prove challenging to learners of English as a second language. Definable as a subtype of multi-word units, or phraseological combinations with various forms, they possess a specific semantic content and pragmatic function, which make them resist decoding and radically diverge from “plain” language, thus giving rise to innumerable comprehension and interpretation problems. Additional features such as the complex use of metonymy and euphemism streamline complex legal processes and manage the emotional and social impact of legal discourse, while strategic adaptations of Grice’s maxims support consistency and interpretive stability. Together, these elements demonstrate that legalese functions not merely as technical jargon but as an essential tool for structuring legal reasoning and administering justice.

-

Keywords: Legalese, collocation, euphemism, comprehension, Grice’s maxims

1. Legal Language: what makes it distinct?

Legal language, also called "legalese" or "legal discourse," is usually defined as a specific type of language used in legal situations to make, understand, and enforce rights, duties, and rules. Its main objective is to make sure that legal materials of various types, including statutes, contracts, rules, and court rulings are clear and easy to understand. Legal language is different from everyday English because it is formed by institutional traditions, procedural requirements, and the necessity for the legal system to be stable and predictable. That is why one of its most important features is "formalism": legal papers often utilize set, formulaic phrases that have been used for hundreds of years because they are clear when interpreted by judges. This includes words like "hereinafter," "thereof," and "whereas," which are never heard in everyday English, but are mostly still used in legal language to keep things consistent and easy to understand. Another important part is its technical/specialized vocabulary, which includes words like "tort," "consideration," "injunction," and "liability", etc., words with very particular meanings that are different from how they are used in common conversation. It goes without saying that such words are part of a legal system that needs particular training to properly understand (

Tiersma, 1999). Legal language typically includes archaic expressions that are still used because they have deep legal meaning and are hard to modify, even though they aren't used much in modern English and can create lots of difficulties for learners of English as a second language.

Another feature worth mentioning in this respect is the syntactic complexity of legal language. Legal writings often have sentences that are quite long and intricate, take numerous turns and focus shifts, and have a lot of subordinate clauses and conditions. This structural complexity helps make sure that all possible situations are covered, but it might make the language hard for people who aren't experts to understand. In legal writing, nominalization (changing verbs into nouns, like "the termination of the agreement" instead of "terminating the agreement") is quite common, with a clear role in enhancing formality: it makes the writing more abstract, formal, and impersonal, decreasing subjectivity and placing the focus on actions instead of people. Legal language is also quite intertextual, since legal papers often refer to other laws, precedents, and rules. This is especially true for anglophone law, or the so-called common-law systems, which lays stress on jurisprudence and legal tradition, i.e. operates by creating a web of legally binding ties between texts. This interconnection strengthens the authority of legal standards and bases interpretation on established doctrine.

Another unique feature of legal language is that it is "performative": legal statements don't just describe reality; they can change it. The words in a sentence from a judge or a contract signed by both parties have legal effects. This performativity comes from the fact that legal language works within institutional contexts that give it power, thus changing reality through words uttered in specific ritualized communicational contexts. Legal discourse is also purposely conservative, putting stability ahead of new ideas. Changes in phrasing can have huge effects on how something is understood, thus legal drafters generally choose classic phrases and collocations that have been clarified by the courts.

However, legal language must be comprehensive and inclusive despite its strictness. This means that it must cover all possible situations and close any gaps that could lead to disagreements. Finally, legal language has a built-in "power dimension": its lack of clarity can create differences between specialists and non-experts, which strengthens the power of legal institutions. In brief, legal language is a distinct, highly regulated, and functionally specialized linguistic system that is quite different from normal speech but serves important social purposes, with special semantic features and a clearly delineated pragmatic dimension, both worth exploring in depth.

2. Legal phraseology: definition, main functions, reasons for existence

Legal phrases, also known as "fixed legal expressions" or "legal formulae," are an important part of legal language and serve important communicative, procedural, and interpretive roles in the legal system. These phrases—like "null and void," "without prejudice," "cease and desist," "force majeure," "beyond a reasonable doubt," and "hereinafter referred to as"—aren't just old-fashioned ways of speaking; they are specialized language tools made to make legal communication clear, stable, and accurate. One of their main aims is to "get rid of confusion": the exact wording of legal documents can make a big difference in the outcome, so standardized phrases give everyone a common, legally tested vocabulary that makes it less likely that there will be different interpretations. Many legal ideas need very specific meanings, so these set phrases work as "shortcuts" to complicated legal ideas that have been worked out through court cases. Another important role is to make sure that legal documents and situations are always the same and easy to understand. Judges, lawyers, and lawmakers use familiar legal terms and the body of interpretations that are associated with them. This makes the law consistent over time and in different places, an essential feature of all law systems. This continuity is important for fairness because it makes sure that similar cases are treated the same way and stops people from changing their minds about how to interpret things just because language trends change.

Legal terms also have "institutional and procedural functions," which help the formal structures of the law. Many legal processes need ritualized or formulaic language to be valid. For example, marriage ceremonies, courtroom decisions, contracts, and laws often include phrases that are required to make the acts legally binding. The phrase "I hereby declare," for instance, is a performative utterance that creates a legal reality instead of describing one. Also, legal terms are needed for categorization and accuracy, especially in systems where laws must apply to a wide range of people and situations. For example, the phrase "terms and conditions" refers to a set of contractual obligations that must be clearly spelled out. "Due diligence," on the other hand, is a legally recognized standard of responsible behavior. Legal phrases serve as conceptual building blocks that organize legal thought, and more often than not literal equivalence is not possible when they are rendered into a different language, even if the legal system is similar.

History, practicality, and the nature of law itself are what make them exist. Legal language has evolved from Latin, French, and Old English traditions, resulting in a complex vocabulary influenced by centuries of judicial interpretation. A lot of legal phrases stay the same because changing them could have unintended effects. For example, changing just one word could create loopholes, change meanings, or make established interpretations invalid. So, legal language is usually deemed as conservative, keeping phrases that have worked in the past. Also, legal phrases exist because the law wants to be "comprehensive and stable", which means it needs to be very clear about what it means to avoid arguments in complicated social situations. Their persistence also shows how specialized the legal profession is: trained legal professionals know how to use legal terms correctly, which keeps legal communication organized and authoritative. In the end, legal phrases stay around because they do important conceptual, procedural, and interpretive jobs that regular language cannot always do, keeping legal norms clear, consistent, and enforceable.

Last but not least, the existence of such phraseology is grounded in the very cultural and professional identity of legal experts, and the condensation of complex and often lengthy legal principles into concise forms with high rethorical impact and memorization potential only adds to the reasons why such formulas exist in legalese.

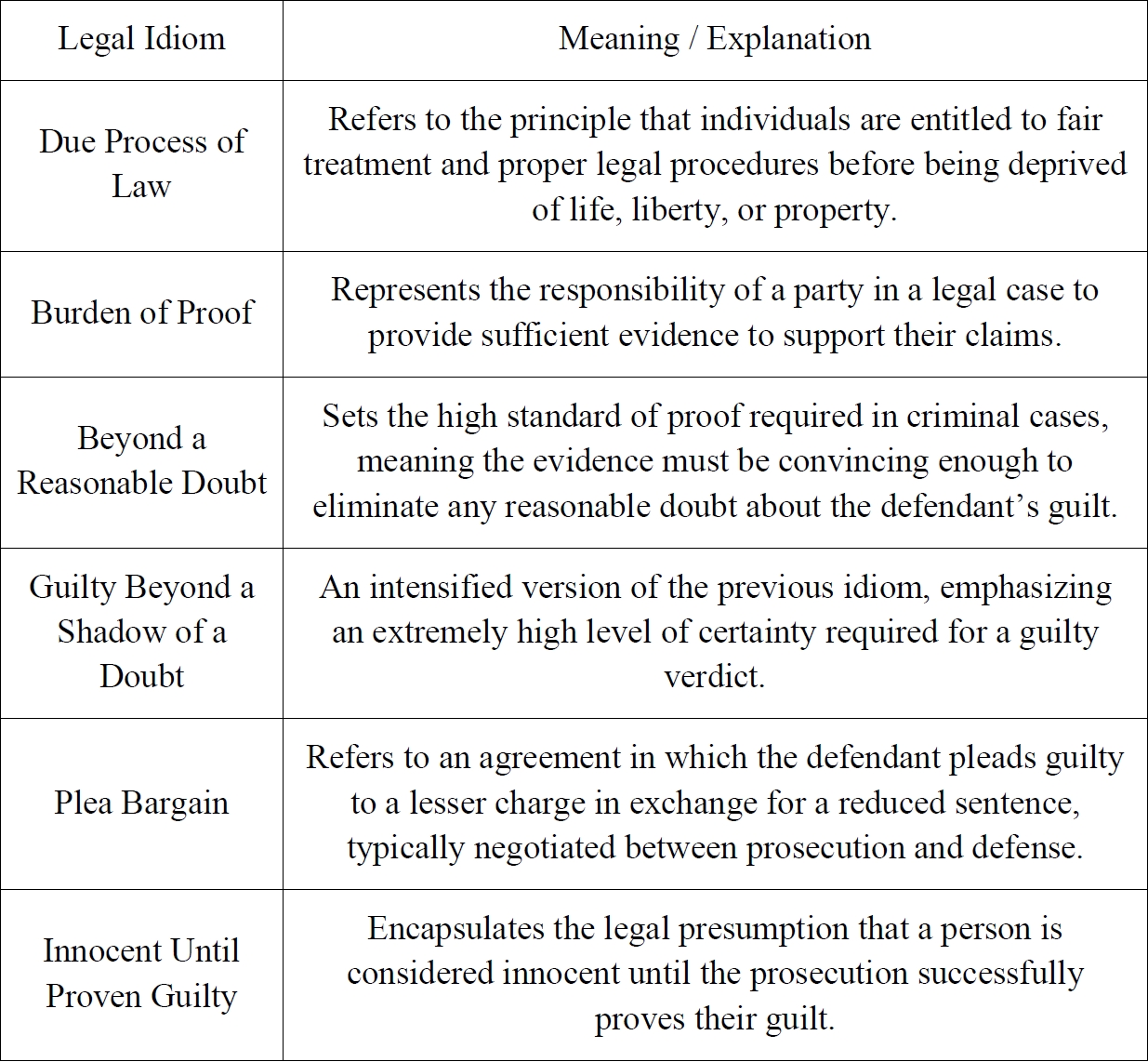

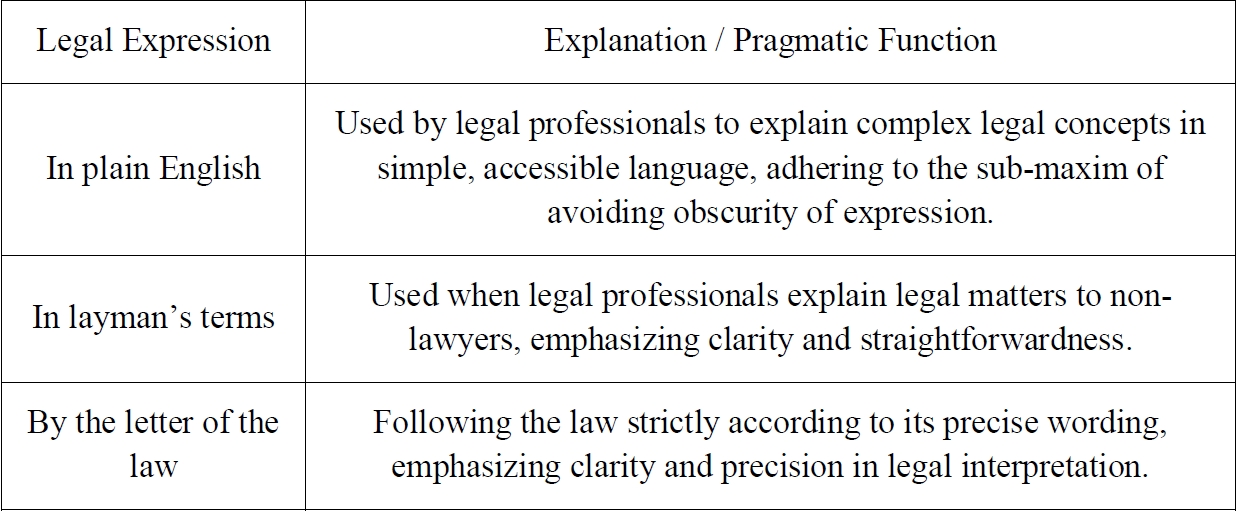

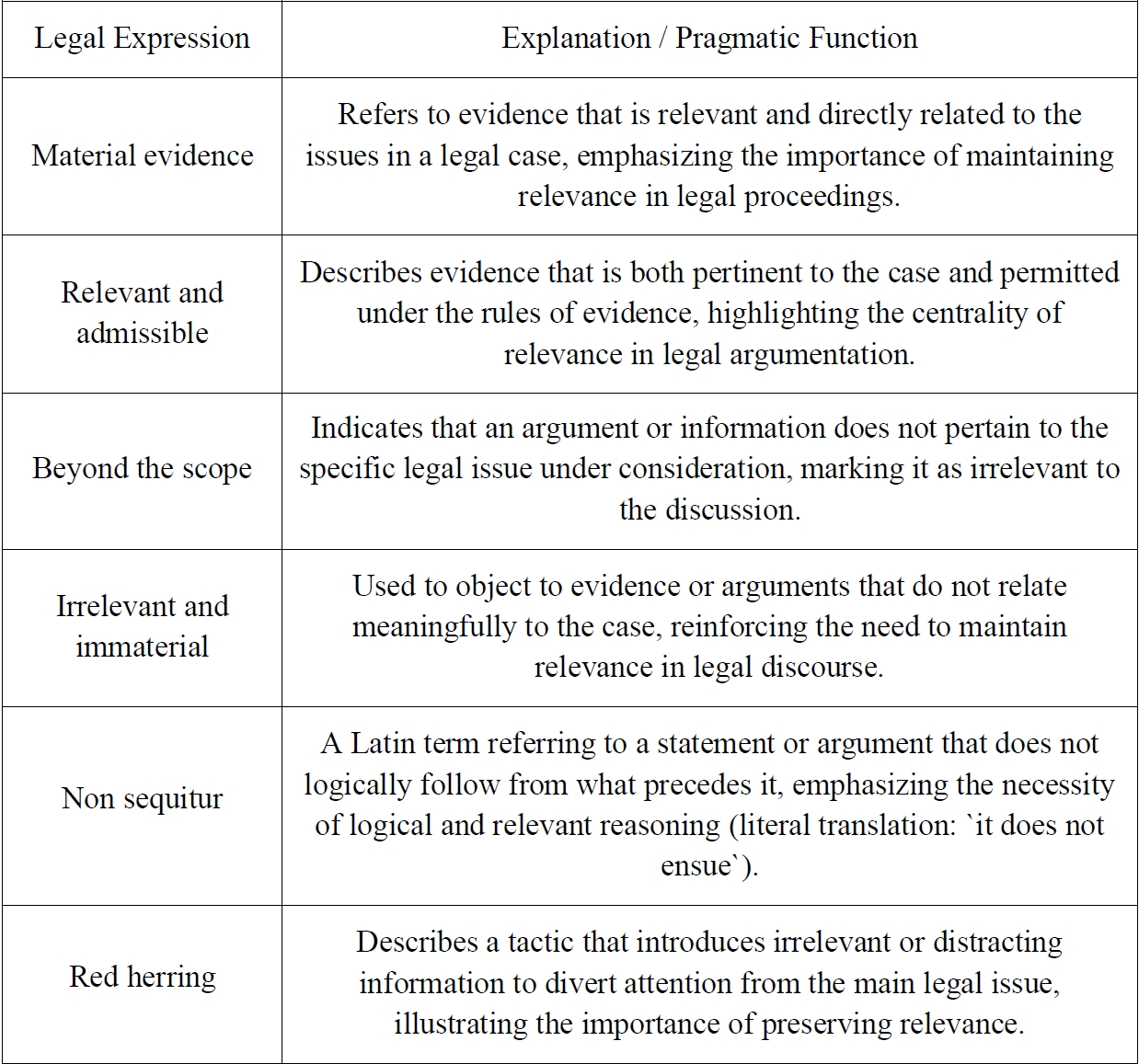

Here are just a few cases in point, illustrating the ability of such ”shorthand” to communicate nuanced and intricate meaning with unmatched efficiency and precision:

3. Pragmatic principles at work in legal phrases

Legal phrases have a lot of practical value in legal communication because they follow a set of rules that make sure they are clear, precise, and stable in meaning. One fundamental principle pertains to Grice's maxims, which influence the conveyance of meaning in cooperative discourse (

Grice, 1975). In legal contexts, it is important to follow the rules of relevance, quality, quantity, and manner to avoid misunderstandings and make sure that legal consequences are based on clear linguistic evidence. Legal phrases also make things more efficient by turning complicated legal ideas into short, easy-to-understand phrases that trained professionals can quickly understand. This is something that studies of legal language often point out (

Tiersma, 1999). This efficiency is closely related to informativeness because these established formulations convey dense legal meaning without needing long explanations, which helps legal systems work more smoothly (

Levinson, 1983).

Another significant aspect of their pragmatic value pertains to the function of conventional implicature. Numerous legal terminologies possess historically and institutionally ingrained implications that transcend their literal meanings, illustrating what

Levinson (2000) characterizes as generalized and context-sensitive interpretive processes. Due to the reinforcement of these implications through frequent usage and judicial interpretation, legal phrases consistently elicit uniform interpretive results across various legal contexts (

Solan, 1993). Legal phrases also depend a lot on presupposition and entailment, which means that they put background assumptions and legally important effects right into the language (

Searle, 1969). These characteristics contribute to the stability of interpretation by establishing certain propositions as axiomatic within legal reasoning, thereby diminishing the likelihood of disputes regarding fundamental premises.

The flexibility of legal language is another reason why it is so powerful. Legal phrases must be adapted to their context so that they work well in statutes, contracts, courtroom arguments, and administrative documents (

Bhatia, 2008). Expert audience considerations also affect how useful they are in real life. Legal language is often used to talk to trained professionals, so legal phrases are useful ways to communicate that assume a shared base of specialized knowledge (

Tiersma, 1999). This common understanding not only makes it easier to share information, but it also makes legal arguments more precise by using terms whose meanings have been widely codified and interpreted by courts.

Legal phrases are important for more than just helping people understand and talk to each other. They are also important for persuasion and rhetoric. Lawyers and judges can use established legal terms in a strategic way to make arguments that have institutional authority and fit with legal tradition (

Solan, 1993). The rhetorical weight of many legal phrases is enhanced by their cultural and historical significance, as they derive from earlier legal systems and bolster the continuity and legitimacy of modern legal practice (

Tiersma, 1999).

Another practical use of legal phrases is to avoid ambiguity. Because the way words are used can affect legal outcomes, using established phrases can help lower uncertainty and stop misinterpretations that could hurt fairness or legal consistency (

Endicott, 2000). Their continued use demonstrates a preference for predictability in legal communication, particularly when judicial precedent has already elucidated their meanings (

Solan, 1993). Finally, legal phrases help people identify as professionals by making the conversation sound specialized and based in institutions (

Bhatia, 2008). Knowing how to use these phrases shows that you are a part of the legal community and follow its rules for communication, which makes legal discourse more authoritative and strengthens professional cohesion.

These practical principles show why legal terms are still necessary in legal communication. Their ability to condense complicated meaning, make sure that interpretations stay the same, and project institutional authority means that they will always be an important part of making legal language clear, coherent, and effective.

3.1 The Maxim of Quantity

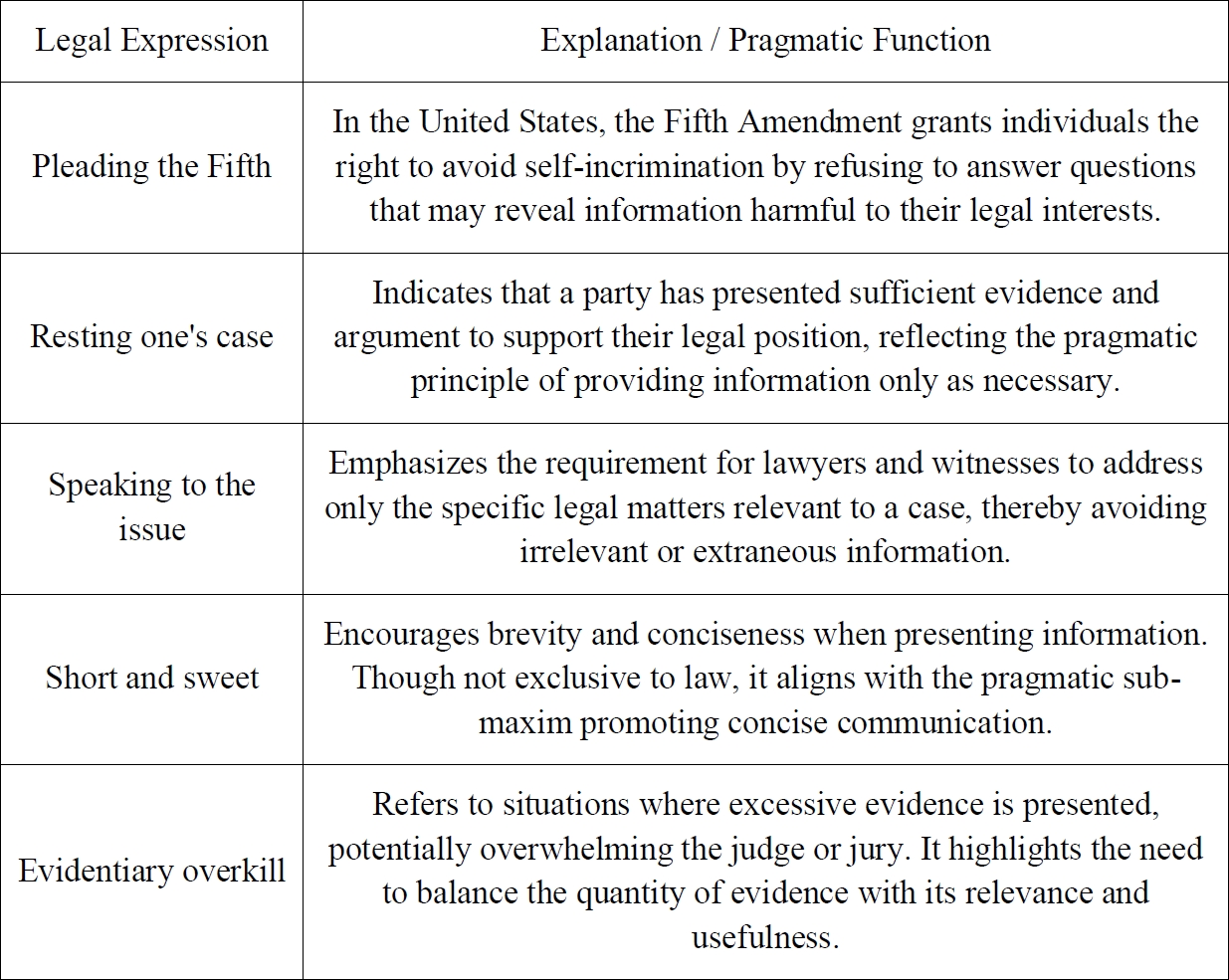

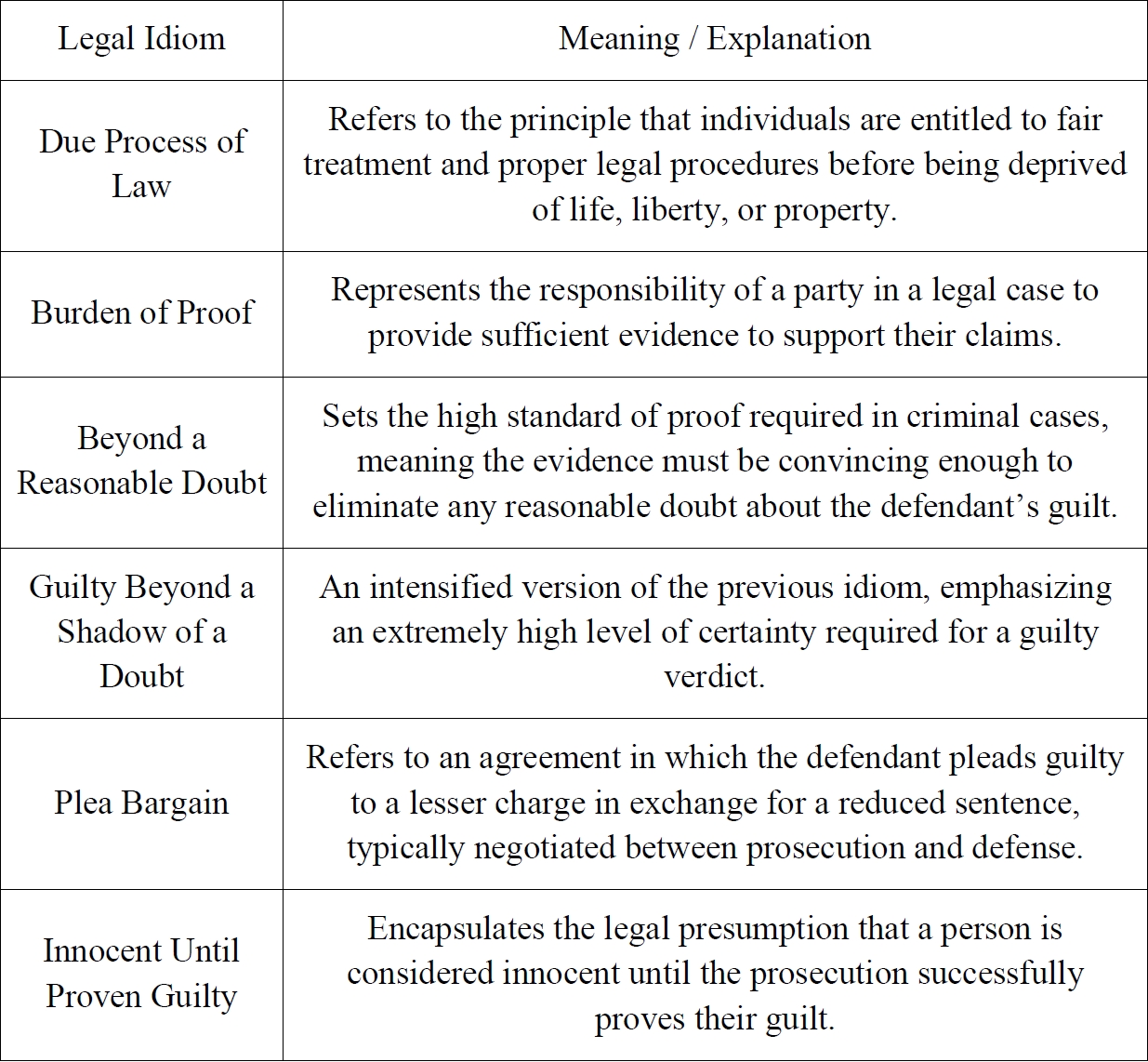

In keeping with these ideas, it is not devoid of interest to examine how Grice’s Cooperative Principle, which aims at guiding efficient communication, is illustrated by certain legal set phrases. The maxim of Quantity focuses on providing the right amount of information necessary in the situation of communication, without any deficit or excess. This need for communicational balance and just the perfect amount of informativeness is to be seen at work in legal language through examples like the following:

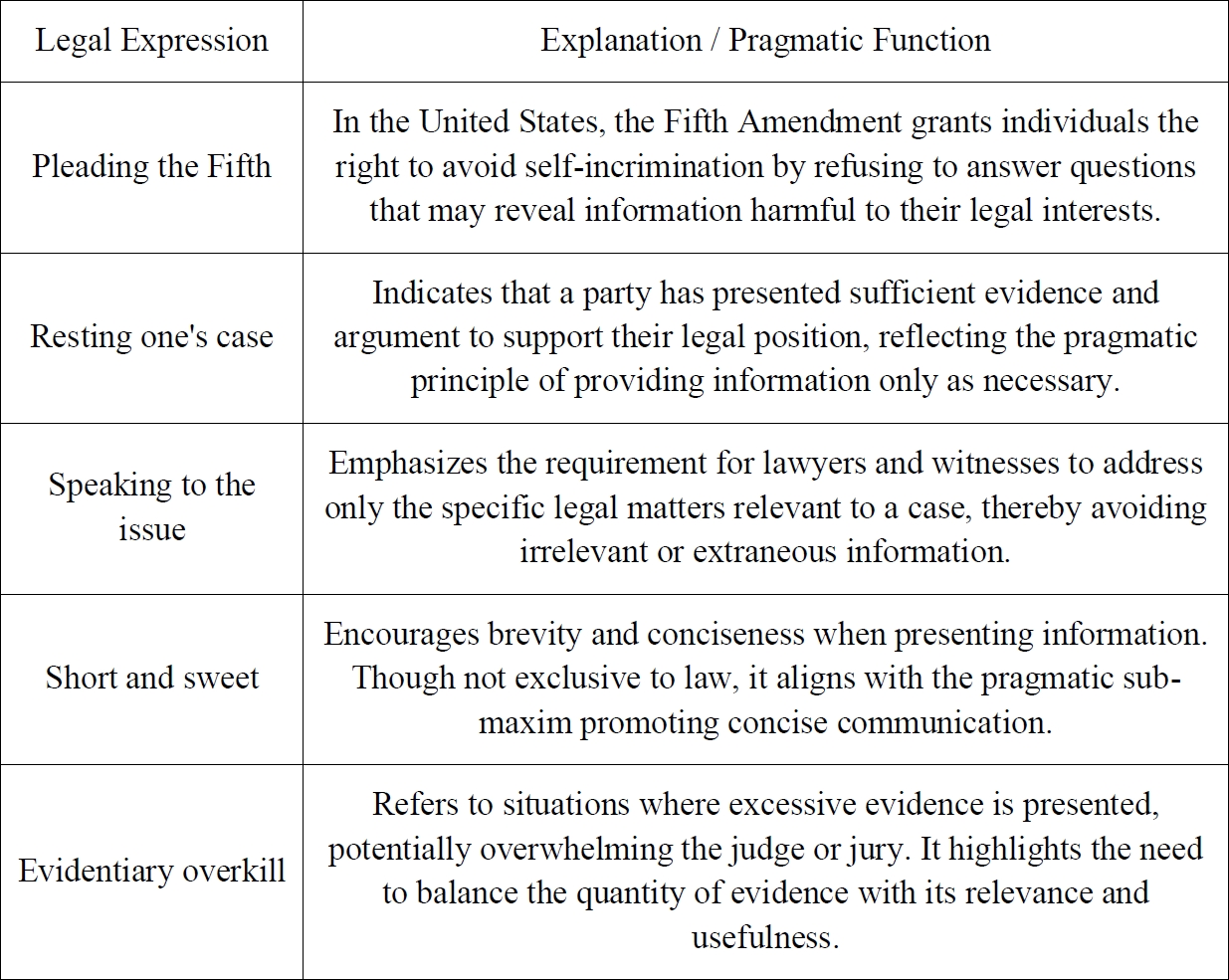

The second maxim devised by

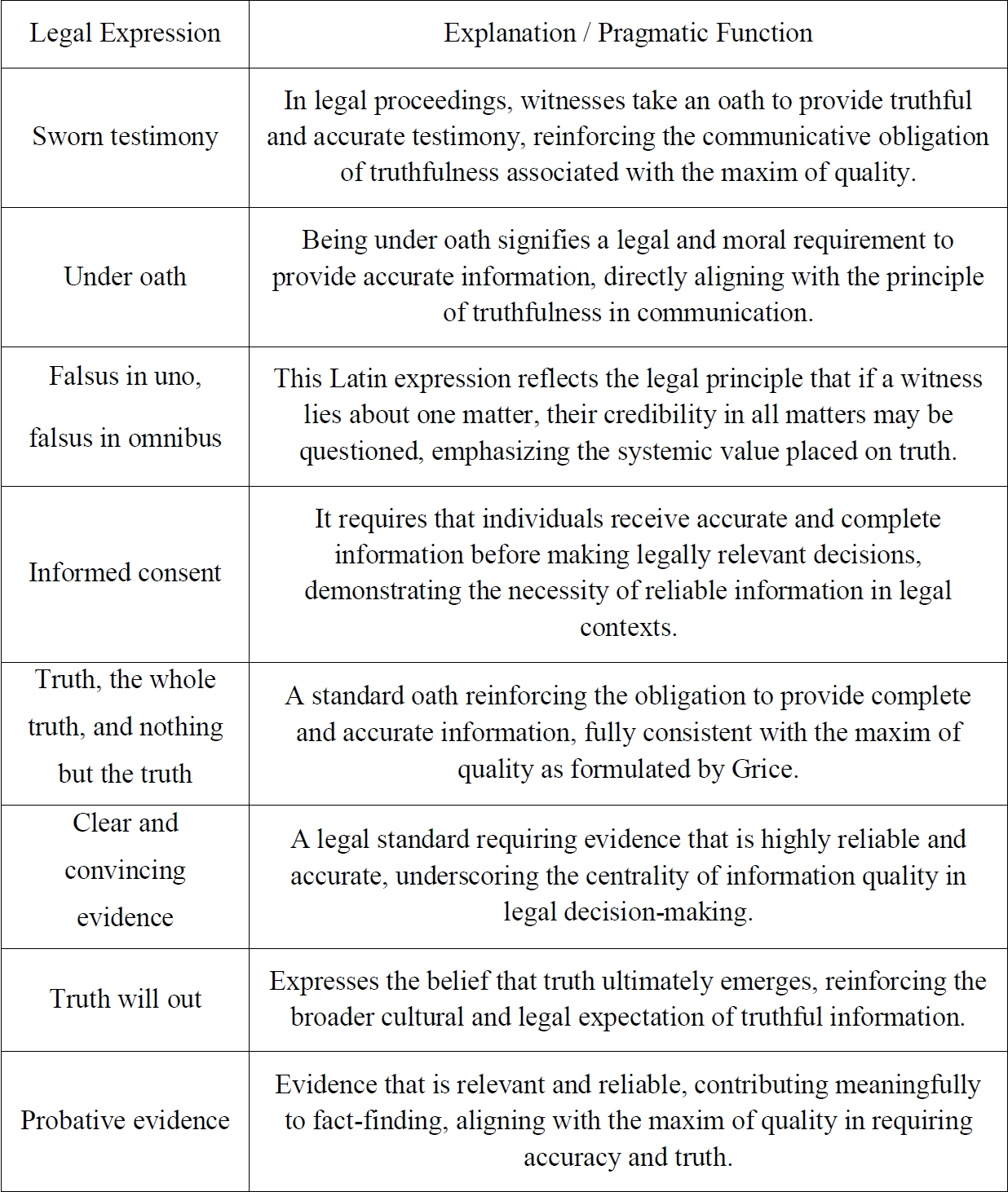

Grice (1975) refers to the crucial role that should be assigned to truthfulness and accuracy in communication, being thus of utmost importance in legal proceedings whose declared purpose is to find out the `truth, and nothing but the truth` and impart justice. Here are just a few examples of how this maxim operates in the deep structure of certain legal set phrases:

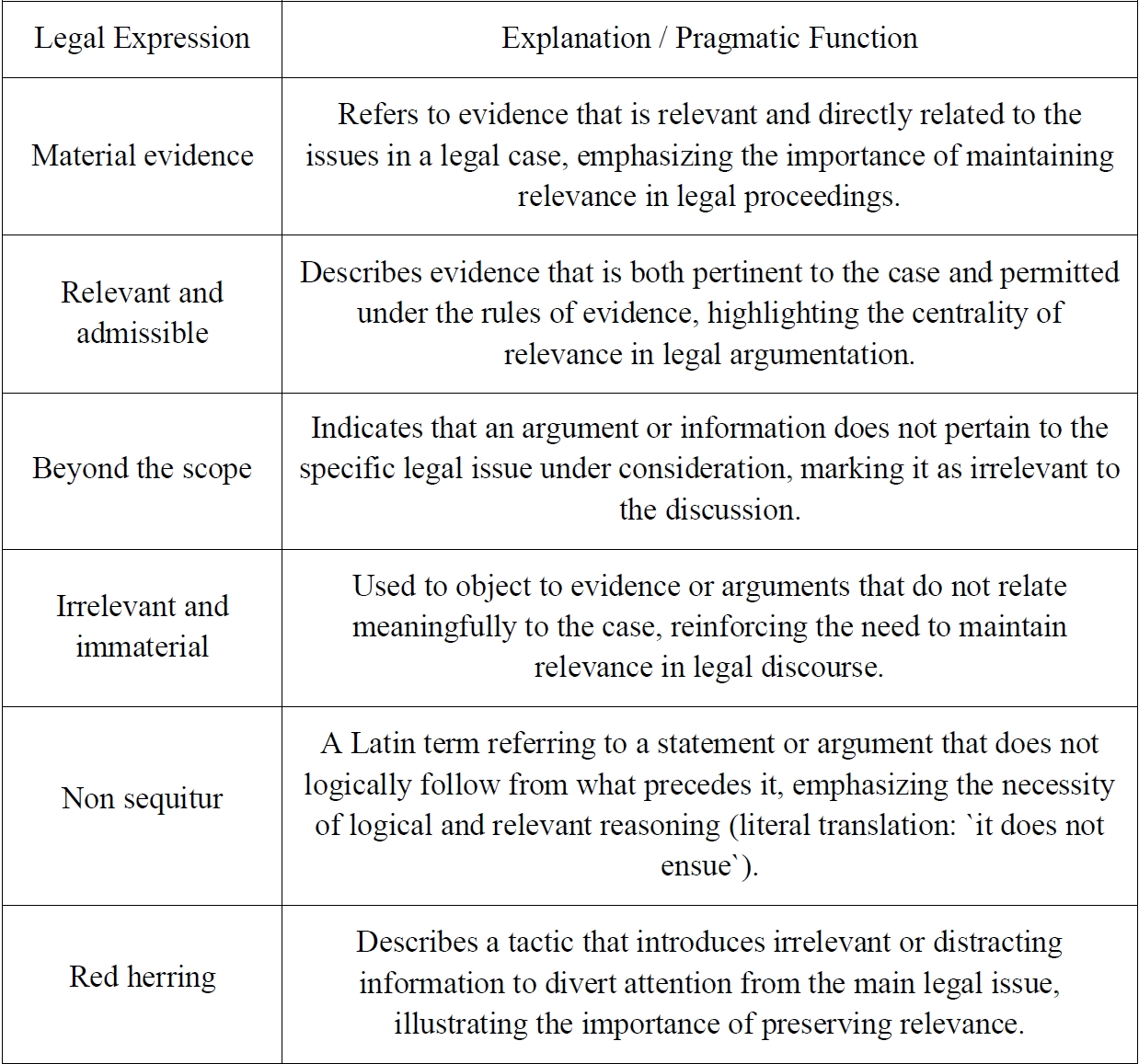

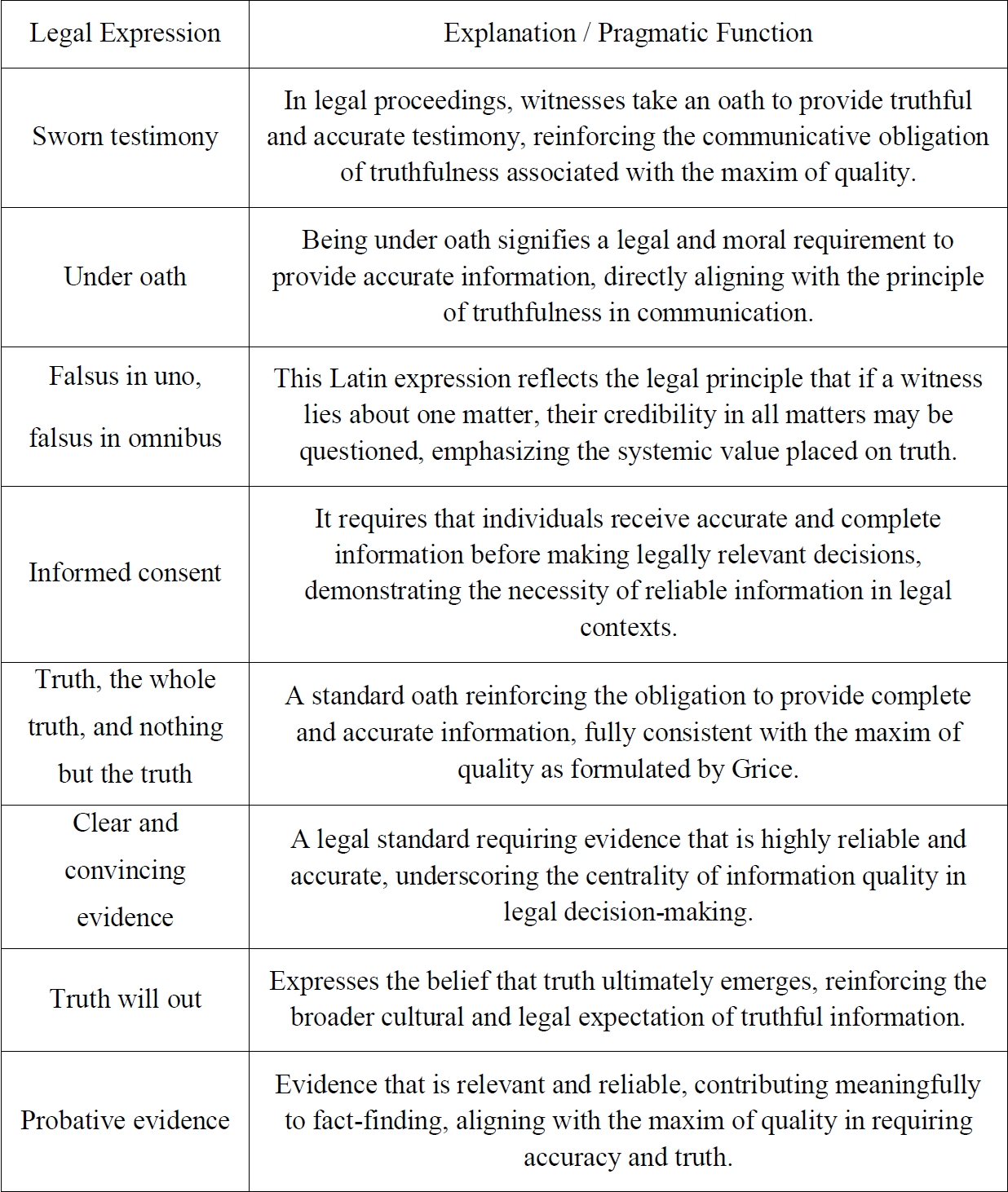

This particular maxim focuses on relevance in communication, which is a must in all professional contexts, not only in legal discourse; however, it seems that relevance is evinced in the case of legal proceedings, where trial time is limited and clarity of judgement should not be obscured by irrelevant details. Instantiations of set phrases that align with this maxim are the following:

Grice's Maxim of Manner—"Be perspicuous", which means avoiding confusion, being brief, and being organized (

Grice, 1975)—is a good way to look at the communication style of legalese. Legal language should, in principle, work to make rights, obligations, and procedures as clear and easy to understand as possible. Nevertheless, legal discourse frequently diverges from the maxim, and these divergences are intentional, reflecting more profound institutional and functional necessities of the legal system, thus occasioning the need for a more in-depth analysis.

First, legalese often doesn't make things clear. Legal texts frequently incorporate antiquated terminology, specialized jargon, and formulaic expressions that lack clarity for non-experts (

Tiersma, 1999). This kind of confusion continues because legal terms get very specific meanings from past cases and professional use, which makes them hard to simplify without risking confusion about what they mean.

Second, legal language tries to be clear, but it is quite difficult to be completely clear because legal ideas are usually really complicated. In fact, legal drafters sometimes intentionally keep things a little vague so that the rules can be applied in a variety of situations (

Endicott, 2000). So, even though the maxim says to be clear, the law often puts accuracy ahead of simplicity, which leads to sentences that are structurally complicated but semantically limited.

Third, legalese often goes against the need for brevity, since legal documents are known for their long sentences, many subordinate clauses, and long lists of conditions. These features are necessary by law to close loopholes, plan for the unexpected, and stop other interpretations (

Solan, 1993). Completeness is prioritized over brevity, indicating a conflict between Gricean efficiency and legal accuracy.

Fourth, legal drafting usually tries to be organized, which is another part of the maxim. However, the way legal texts are put together can still be hard to understand because they have definitions, exceptions, conditions, and cross-references that are arranged in a hierarchy. From a legal point of view, this organization makes sense, but to people who aren't lawyers, it might seem confusing (

Bhatia, 2008).

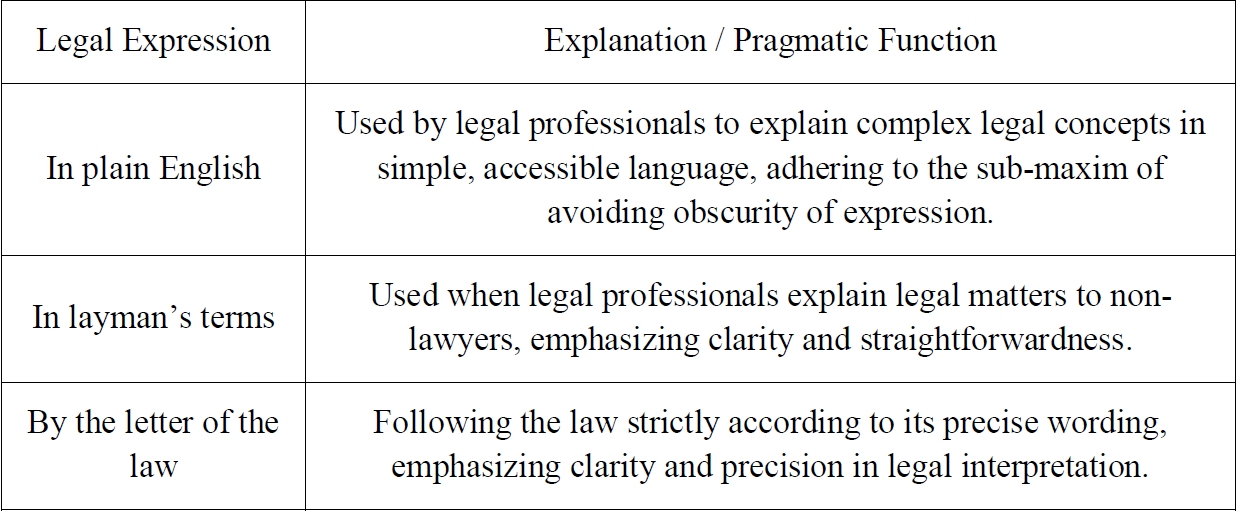

So, unlike the previous maxims, which are generally observed without reservations, the Maxim of Manner may sometimes be flaunted for practical reasons, i.e. immediate clarity can be sacrificed in order to increase the reliability of legal interpretations and as a communication strategy useful in the convoluted argumentation of legalese. In any case, a number of possible illustrations of the maxim may still be found in several set phrases, as follows:

It is noteworthy that these illustrations are considerably less numerous than for the other maxims, which is an additional argument in favour of the special status of this particular maxim in legalese.

4. Semantic aspects in legal phrases

As stated previously, legal collocations and expressions have a lot of different meanings that make them hard to understand and unique in legal language. One significant aspect is their dependence on figurative language, enabling the articulation of abstract legal concepts through metaphorical or symbolic formulations (

Gibbs, 1994). This figurative aspect frequently intersects with polysemy, as numerous legal set phrases encompass terms with multiple interconnected meanings, necessitating interpreters to determine the legally pertinent interpretation based on context (

Cruse, 2004). but one particular trope, metonymy, often manifests in legal terminology, facilitating indirect references to institutions, actions, or legal consequences through associated terms (

Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). The most commonly used example in this respect may be `the Bench` (the panel of judges traditionally sitting on wooden benches in court), `the Docket` (the cases being ruled over`) and even the more complex the `long arm of the law`, alluding to the implacability of the judicial process, which ultimately imparts justice despite potential delays and other impediments. These semantic characteristics highlight the importance of contextual meaning, as legal idioms seldom derive their significance solely from literal interpretation; rather, they rely on situational factors and institutional frameworks to ascertain their intended meaning (

Levinson, 1983;

Searle, 1969).

Another fundamental semantic feature is semantic bleaching, a process whereby repeated usage diminishes originally robust lexical meanings over time, leading to expressions that serve more as fixed legal markers than as significant lexical combinations (

Traugott & Dasher, 2002). Interpretation is further influenced by the historical and cultural significance inherent in legal set phrases, many of which derive from prior legal systems and retain remnants of those traditions (

Tiersma, 1999). This historical basis is closely related to collocational restrictions, which limit the situations where legal idioms can be used correctly. These restrictions stem from enduring legal conventions that determine which terms typically co-occur, thereby bolstering the stability and institutional legitimacy of idioms (

Sinclair, 1991).

Legal expressions also have meanings that are related to the fact that legal reasoning is inherently complicated. Ambiguity and vagueness often present challenges, as numerous legal terms must reconcile broad applicability with interpretative adaptability (

Endicott, 2000). Ambiguity can be an issue, but strategic vagueness lets legal principles stay flexible in different situations and cases. Many legal idioms also encode legal principles and concepts, breaking down complex doctrinal ideas into short phrases that make it easier for lawyers to think (

Solan, 1993). This process inherently facilitates the delineation of legal distinctions, as idioms assist in the precise categorization and differentiation of legal states, actions, or consequences (

Bhatia, 2008).

Legal collocations are also very important for analogical reasoning, which is one of the main ways that legal arguments are made and judged (

Llewellyn, 1930). Their meanings may be augmented or elucidated through comparison with analogous legal contexts, thereby increasing their explanatory efficacy. Lastly, the meaning of legal idioms is closely tied to the situation in which they are used, since how they are understood depends on who is speaking, where they are, and why they are speaking (

Grice, 1975;

Levinson, 2000). The interaction between semantics and pragmatics keeps legal phrases flexible and authoritative language tools that can convey complicated legal meaning while keeping the legal system stable.

5. The Special case of euphemisms in legalese

As suggested before, when mentioning semantic bleaching, euphemisms in legalese are strategic linguistic tools that make harsh or controversial legal realities less harsh, less clear, or more positive, softening their markedly negative impact on the interlocutor. They are based on both institutional norms and practical concerns, and abound in legal discourse as their role is to alleviate the emotional or social ramifications of legal actions, thereby preserving the formality, neutrality, and authority of legal institutions (

Tiersma, 1999). For instance, "collateral damage" is a euphemism for unintended harm to civilians, and "correctional facility" is a less direct way of saying "prison," which makes penal institutions seem less serious. "Termination of employment" is another way of saying "firing," and "involuntary manslaughter" is another way of saying "killing someone without intent/accidentally". In court, people also make abundant use of euphemisms. For example, "passed away" might be better than "died," especially in cases that are sensitive for victims or their families (

Solan, 1993). These linguistic choices can serve pragmatic functions such as facilitating politeness, maintaining institutional decorum, and preventing unnecessary emotional escalation, all of which contribute to communicative efficiency within adversarial settings (

Levinson, 1983).

In addition, legal euphemisms frequently mirror institutional power dynamics by obscuring responsibility or diffusing accountability, exemplified by terms such as “officer-involved shooting,” which circumvents the direct assertion that a police officer shot an individual (

Bhatia, 2008). Euphemisms are very important in shaping how people see, understand, and talk about legal events, suggestively illustrating how language, power, and legal reasoning all work together in a rather complicated manner.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, the examination of these phraseological units in legal terminology reveals that legal language, or legalese, constitutes a highly specialized communicative system influenced by both semantic complexity and pragmatic necessity. Utilizing Grice’s maxims—especially those concerning quality, quantity, relevance, and manner—demonstrates that legal discourse often alters, adjusts, or intentionally deviates from standard conversational conventions to attain precision, stability, and institutional authority, as well as the necessary persuasive power in a formal context of communication. Legal expressions, encompassing specialized idioms, formulaic phrases, or performative utterances, possess conventionalized meanings that have been solidified through precedent and professional practice, thereby guaranteeing predictability and consistency across legal contexts. Simultaneously, devices like metonymy and euphemism demonstrate how legal language reconciles directness with sensitivity, formality with functionality, and abstraction with communicative efficiency. Metonymic phrases like "the Court" or "the Crown" simplify complicated institutional processes into easy-to-understand language, while lessening the emotional or social effects of legal actions, which is in line with the decorum and neutrality that is expected in legal settings. Through these features, legalese becomes more than just technical jargon; it becomes a complex language system that shows and strengthens the values, limits, and power structures of the legal world. In the end, the practical and semantic aspects of legal language show how important it is for shaping legal reasoning, guiding interpretation, and promoting both clarity and authority in the administration of justice.

Figure 1.Examples of Common Legal Idioms and Their Explanations

Figure 2.Legal Expressions Illustrating the Maxim of Quantity

Figure 3.Legal Expressions Illustrating the Maxim of Quality

Figure 4.Legal Expressions Illustrating the Maxim of Relation

Figure 5.Legal Expressions Illustrating the Maxim of Manner

REFERENCES

- Austin, J. L. (1962). How to Do Things with Words. Oxford University Press.

- Bach, K. (1994). Conversational Implicature. " Mind & Language, 9(2-3), 124-162.

- Bhatia, V. K. (2008). Legal Discourse: Analysis, Regulation, and Representation. Continuum.

- Carston, R. (2002). Thoughts and Utterances: The Pragmatics of Explicit Communication. Blackwell Publishing.

- Cruse, D. A. (2004). Meaning in language: An introduction to semantics and pragmatics (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Endicott, T. (2000). Vagueness in law. Oxford University Press.

- Fillmore, C. J. (1977). "Scenes-and-Frames Semantics.". In P. N. Johnson-Laird & P. C. Wason (Eds.), Thinking: Readings in Cognitive Science (pp. 263-289). Cambridge University Press.

- Gibbs, R. W. (1994). The Poetics of Mind: Figurative Thought, Language, and Understanding. Cambridge University Press.

- Grice, H. P. (1975). "Logic and Conversation.". In P. Cole & J. L. Morgan (Eds.), Syntax and Semantics: Speech Acts (Vol. 3, pp. 41-58). Academic Press.

- Green, G. M. (1999). Pragmatics and Natural Language Understanding. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Horn, L. R. (1984). "Toward a New Taxonomy for Pragmatic Inference: Q-based and R-based Implicature.". In D. Schiffrin (Ed.), Meaning, Form, and Use in Context: Linguistic Applications (pp. 11-42). Georgetown University Press.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press.

- Levin, B. (1993). English Verb Classes and Alternations: A Preliminary Investigation. University of Chicago Press.

- Levinson, S. C. (1983). Pragmatics. Cambridge University Press.

- Levinson, S. C. (2000). Presumptive Meanings: The Theory of Generalized Conversational Implicature. MIT Press.

- Llewellyn, K. N. (1930). The bramble bush: The classic lectures on the law and law school. Columbia University Press.

- Palmer, F. R. (1981). Semantics. Cambridge University Press.

- Recanati, F. (2004). Literal Meaning. Cambridge University Press.

- Reuland, E. (2001). Pragmatic Interpretation and the Resolution of Ambiguity. Linguistics and Philosophy, 24(5), 671-731.

- Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. Cambridge University Press.

- Sinclair, J. (1991). Corpus, concordance, collocation. Oxford University Press.

- Solan, L. M. (1993). The language of judges. University of Chicago Press.

- Sweetser, E. (1990). From Etymology to Pragmatics: Metaphorical and Cultural Aspects of Semantic Structure. Cambridge University Press.

- Tiersma, P. M. (1999). Legal Language. University of Chicago Press.

- Traugott, E. C., & Dasher, R. B. (2002). Regularity in semantic change. Cambridge University Press.